Recent changes to Google’s search algorithms and advertising policies have radically reshaped the flow of online information about holistic medical alternatives.

Recent changes to Google’s search algorithms and advertising policies have radically reshaped the flow of online information about holistic medical alternatives.

The moves have had significant impact on many websites that promote natural alternatives—including Holistic Primary Care’s—and they raise profound questions about freedom of information and the role of major online platforms in mediating online medical dialog.

At HPC, we became aware of the changes last March, when we noticed a sudden, surprising, and significant downturn in traffic on our website.

Over the previous 18 months, our traffic had been building steadily thanks to a comprehensive SEO (search engine optimization) strategy beginning in late 2017. So, we were shocked to see a 77% drop over a 10-day period in mid-March.

Josh Whitehurst, our IT consultant was baffled. There’s a predictable internet-wide traffic drop around the Spring Break season. But it’s never so drastic, or so longstanding.

Re-Routing Traffic

We soon realized we were not alone, thanks to posts by integrative medicine journalist John Weeks. In his blog, The Integrator, Weeks reported that in roughly the same time frame, many other natural medicine websites also experienced big drops.

Dr. Joe Mercola saw a staggering 99% drop in visitors to his popular site, www.mercola.com. Dr. Andrew Weil’s www.drweil.com saw a 66% decline. Sayer Ji’s GreenMedInfo saw an 81% reduction in the site’s search visibility on Google. MindBodyGreen reported a 55% drop. Lynn McTaggart, a journalist who was among the first to sound the alarm, lost half of the usual traffic on her popular site, What Doctors Don’t Tell You.

Joe Cohen, CEO of SelfHacked.com –a self-care site–saw a 94% drop. Kelly Brogan, MD, a functional medicine psychiatrist, reported that her site which averaged over 225,000 impressions per month, flatlined in early June.

Supplement companies and educational organizations in the holistic/functional medicine sphere have also seen big, unexpected, and seemingly unexplainable traffic drops.

What happened?

Google phased in a series of changes to its keyword search algorithms starting in the summer of 2018. The big one, known in IT circles as “Medic Update 2” kicked in in March 2019. In aggregate, these changes have systematically demoted information about alternatives to conventional medicine, or that have links to sites and topics that Google deems problematic. “Detox” and “vaccines” appear to be red-flag subjects, but there are others.

Sites and stories that last year would have appeared within the top 10 returns on a Google search are now buried on the 4th or 5th page of the search return, or even further down, where few viewers will scroll.

Since a website’s traffic depends largely on the visibility of its content on search returns, lower visibility translates into fewer visitors. For many sites, that means less revenue.

EAT It!

In short, Google is now refereeing—some would say censoring–certain types of health information. But it is not doing so by blacklisting specific sites or topics; that’s  primitive and old-school. The new approach is more refined: Google’s new search algorithms preferentially shunt information seekers toward or away from certain sites, based on new credibility criteria that Google has termed, “EAT.” It stands for “Expertise,” “Authority,” and “Trust.”

primitive and old-school. The new approach is more refined: Google’s new search algorithms preferentially shunt information seekers toward or away from certain sites, based on new credibility criteria that Google has termed, “EAT.” It stands for “Expertise,” “Authority,” and “Trust.”

“Google wants to make sure that they are showing results from websites that have all three of these,” explains David LeFlore, Chief Technology Officer at Nuclear Networking, a Colorado-based consultancy that helps companies optimize their web presences.

But LeFlore stresses that many things besides the content quality can affect a website’s “edibility.”

“This doesn’t mean that the sites that lost rankings during this update don’t possess “EAT.” It could mean that it wasn’t communicated properly through site optimization and backlinks to the search engine.

Google penalizes sites that overuse the robot’s “crawl budget,” meaning that sites that have a lot of broken or misdirected links, overly long content titles, slow page loading speeds, or other data architecture issues can be demoted, even if their content is highly credible.

But it is clear that Google’s main intention with EAT is to squelch content the company considers questionable.

But it is clear that Google’s main intention with EAT is to squelch content the company considers questionable.

Google classifies sites that host health or medical information under its “Your Money, Your Life (YMYL)” category. The company has stated “We have very high Page Quality rating standards for YMYL pages because low-quality YMYL pages could potentially negatively impact users’ happiness, health, financial stability, or safety.”

Google’s Quality Rater Guidelines for health topics are particularly concerned with “fake news, dubious claims & clickbait.” The company says its updated algorithms will favor, “people or organizations with appropriate medical expertise or accreditation.” But there’s little detail about how Google is defining “appropriate” expertise.

Is it Legit(Script)?

In evaluating content related to dietary supplements and other natural products, Google relies largely on an outside company called LegitScript, an independent website rating and certification entity whose self-defined mission is to “inform businesses, governments, and the public about which commercial entities are legitimate, legal, and trustworthy—and which are not.”

LegitScript holds that “Certification helps legitimate pharmacies, telemedicine providers, supplement websites, addiction treatment facilities, and CBD products and merchants show the highest level of credibility.”

LegitScript is a pay-to-play opportunity: to obtain certification, a company or website pays an application fee of $2,495, after which LegitScripts raters review the site for “problematic products, ingredients, and marketing claims.”

If the raters consider the site credible and problem-free, the company receives a certificate—and search engines are notified that the site is certified. The certification minimizes the risk that Google, Yahoo, and others will block a site—so long as the company continues to pay a $3,995 annual maintenance fee.

Google takes the position that its filtering of search results is done for the public good, to protect viewers from fraudulent, untruthful, or commercially-motivated medical information.

There’s no question that the internet is rife with bogus claims, questionable products and practices, unproven speculations, and shameless marketing.

But it is also brimming with reasonable and honest content on a wide range of health topics and medical disciplines. Some are outside conventional “standards of care.” But that doesn’t make them inherently fraudulent or misleading. Many valuable healing modalities are not currently included in mainstream care standards, while many questionable approaches continue to be accepted as “standard” in conventional medicine.

Google’s Quality Rater Guidelines state that: “High quality information pages on scientific topics should represent well-established scientific consensus on issues where such consensus exists.”

And therein lies the rub: there are many medical issues on which there is little consensus. Further, consensus on healthcare issues changes frequently. History shows that many “well-established” consensus-based truths are overturned over time. Will Google’s algorithms keep pace with the ebb and flow of medical research?

The real question here is whether Google—a commercial profit-driven search engine platform—is an appropriate arbiter of medical information. Secondarily, if the company is going to actively influence what an internet searcher is likely to see, does it not have an obligation to publicly disclose its filtering criteria?

Google has acknowledged changes to its algorithms. These happen fairly often, from minor tweaks to major updates. They’re part of an iterative process to improve Google’s services. In September, for example, Google announced that its algorithms will favor sites that host original news reporting over those that curate content from other sources.

But Google is not always transparent about the specific changes it makes. As a privately held corporation, it is not obliged to share those details.

Black Boxes

“Google’s front-facing announcement was, “This is in the interest of public health, and there’s a lot of fake news out there.” But there’s a black box here, that we’re never going to be able to see into. I do believe that their front-facing reasoning—what they tell us—is not entirely representative of the truth,” says Josh Whitehurst, principal at Pinnacle Digital, a digital marketing consultancy based in Little Rock, AR.

going to be able to see into. I do believe that their front-facing reasoning—what they tell us—is not entirely representative of the truth,” says Josh Whitehurst, principal at Pinnacle Digital, a digital marketing consultancy based in Little Rock, AR.

In theory, the algorithm changes apply uniformly and blindly to all information on the web, thus creating a level and objective playing field. In practice, it’s a different story.

Keep in mind that algorithms do not arise by themselves (not yet, anyway).

“Humans with opinions create algorithms,” says Tyler Horsley, principal of Nuclear Networking. Horsley’s team is currently working with supplement companies and others in the natural medicine space adversely affected by the Medic 2 update.

Google promotes the idea that its algorithms are objective and unbiased. Horsley contends that in reality, these systems are influenced by the people who program them–people with opinions and objectives of their own.

Beyond the algorithms, Horsley says Google is also applying what are termed “manual penalties” to certain topics and certain sites.

This means actual people employed or contracted by Google look at sites red-flagged by the “blind” automated algorithms. These reviewers assess a site’s “link neighborhood”—the concentric circles of other sites, articles, and opinion-leaders to which the site in question is cross-linked.

Based on this, and other opaque, undefined factors like “trust flow,” the raters can manually up- or down-grade a website’s search ranking. This in turn affects where in a search return the site’s content will appear.

In other words, your site can be deemed guilty by association. If it contains a lot of links to people or topics that Google has already deemed problematic, it could be downgraded—without your knowledge. Google does not notify you of a downgrade, nor does it give reasons or suggestions for remediation.

Suggestive Behavior

Predictive auto-search suggestions are another means by which Google—intentionally or unintentionally–mediates information flow across its platform. This is the function that gives you a list of potential search phrases when you type a word or name into the Search box.

Google claims its auto-search suggestions are automatically generated by the “data lake”–the vast aggregation of search topics that emerges organically from millions of people using the tool to look up particular topics.

According to Zach Vorhies, a former software engineer at Google/YouTube, that lake is being “poisoned.”

Vorhies left the company several years ago after becoming convinced that Google’s algorithms were unfairly biasing political information toward the Democratic party’s political agendas. He has since positioned himself as a whistleblower, sharing thousands of company documents with rightward leaning political media like the Veritas Project, as well as to the Department of Justice.

Vorhies claims Google deliberately biases auto-searches on certain topics—including hot medical issues like vaccines. He and others who agree with him have yet to prove that, and it would be easy to dismiss him as a wingnut conspiracy theorist.

However, cursory experiments with auto-search do raise questions.

For example, I recently typed the phrase “Supplements are” into the search window. Google suggested the following: “Bad,” “Dangerous,” “scams,” “a waste of money,” “garbage,” “not regulated by the FDA,” “are they good for you” and “worthless.”

Then I typed in, “Pharmaceuticals” and got the following: “Definition,” “near me,” “companies in NJ,” “in our water supply” and “jobs in”.

If we are to believe Google that its auto-suggestions emerge organically from the hive mind, my experience means that millions of people are actively looking for jobs in pharma, and millions of others are seeking information proving that supplements are fraudulent.

I find that hard to believe.

I tried the same experiment again several weeks later, and on both keywords (“supplements” and “pharmaceuticals”) the auto-suggestions were much more neutral (e.g. “supplements near me” “supplements for memory” “pharmaceuticals definition of” “pharmaceutical stocks”).

Google’s auto search suggestions do change over time, and very likely this is driven blindly by user search trends. But that doesn’t rule out the possibility that the company can potentially bias this function.

It Ads Up

One could argue that a modicum of online content filtering is a good thing, and that in refereeing medical information Google is not inherently biased toward any particular medical philosophy or treatment approach.

But take a close look at the company’s advertising policies and practices, and the bias emerges more clearly.

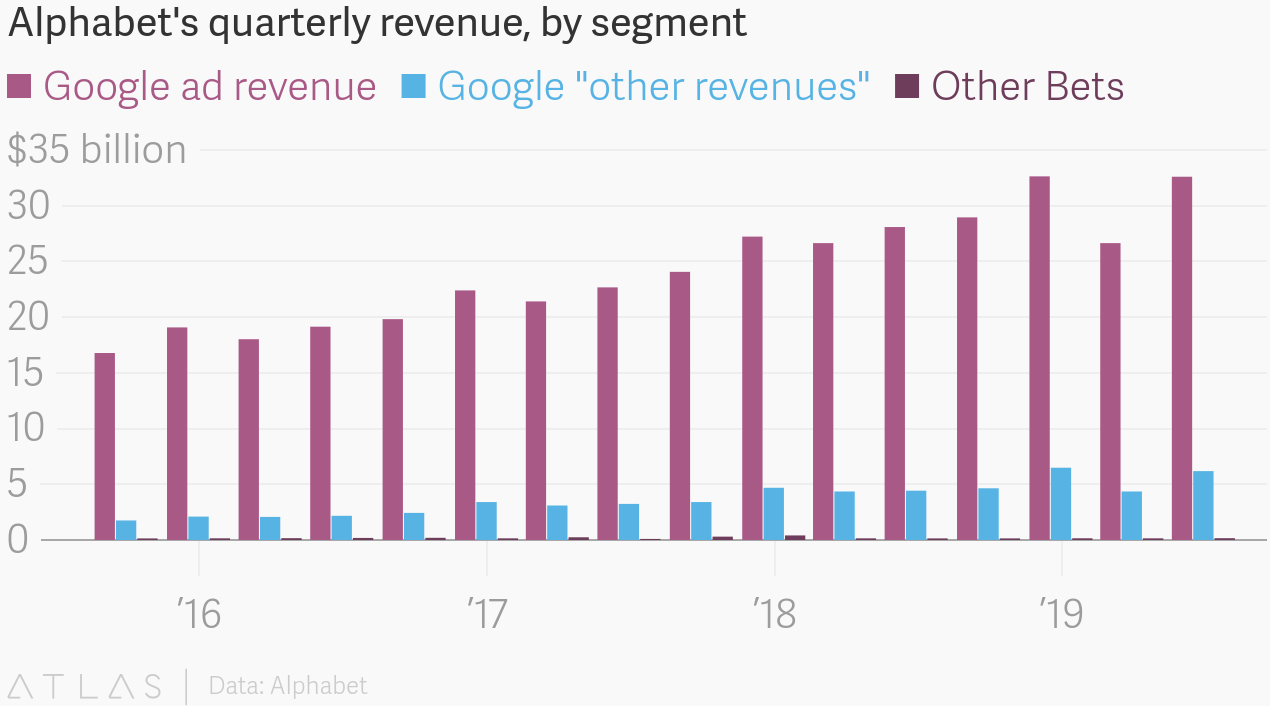

First, understand that Google’s total revenue in 2018 was $136.8 billion—an aggregate revenue growth of 23% over the previous year. Ad revenue amounted to $116.3 billion, or 85% of the total.

First, understand that Google’s total revenue in 2018 was $136.8 billion—an aggregate revenue growth of 23% over the previous year. Ad revenue amounted to $116.3 billion, or 85% of the total.

In its 2018 annual report filing with the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), Alphabet Inc.—Google’s parent company—states: “The goal of our advertising business is to deliver relevant ads at just the right time and to give people useful commercial information.”

Alphabet’s executives go on to state that, “We, like others in the industry, face other violations of our guidelines, including sophisticated attempts by bad actors to manipulate our advertising systems to fraudulently generate revenues for themselves or others, or to otherwise generate traffic that does not represent genuine user interest or intent. While we invest significantly in efforts to detect and prevent invalid traffic, including attempts by bad actors to generate income fraudulently, we may be unable to adequately detect and prevent such abuses in the future.”

Google says it allocates vast resources to stopping bad ads, and removes billions of them every year.

Concurrent with the Medic 2 search algorithm update, Google revised its Adsense policies and now explicitly prohibits ads that promote, “speculative and/or experimental medical treatments.”

Specifically, the company names things like stem cell therapy, other non-stem cellular therapies, gene therapy, regenerative medicine, platelet-rich plasma injections, biohacking, and “do-it-yourself genetic engineering products and gene therapy kits.”

But the “speculative and/or experimental” net is wide enough to catch the majority of dietary supplements and holistic medical approaches, depending on how strictly Google applies the randomized controlled trial standards.

Swift Impact

The impact of the new ad policy has been swift. Supplement companies, medical organizations, and individual practitioners whose ads were formerly acceptable to Google, are suddenly getting rejection notices.

Among those hit hard is the Academy of Integrative Health and Medicine (AIHM). Executive Director, Tabatha Parker, ND, says that for years, the organization has been running ads on Google to attract new members and promote its conferences. This year, Google rejected 21 of AIHM’s ads.

The content of the rejected ads did not differ substantially from the ones Google previously accepted.

Parker tells Holistic Primary Care that AIHM appealed the rejections. “Whenever the automation disapproves you, you can request a manual review, and a live human team looks at your ads and decides whether to approve or not.”

looks at your ads and decides whether to approve or not.”

After two lengthy rounds of review, Parker was able to win approval for most of AIHM’s ads. But she says the process was lengthy, time-consuming and exhausting. It also impeded AIHM’s promotional efforts.

Google has also rejected ads from clinics providing “experimental” procedures that were previously considered acceptable to the search platform.

Even before the recent ad policy change, Google’s AdSense platform already favored Big Pharma over the supplement/nutraceutical industry.

AdSense categorizes the pharmaceutical and supplement industries together under a single header for “Drugs and Supplements” rather than making them distinct categories.

In so doing, Google allows drug companies (or shell websites created by them) to leverage their vast spending power to bid up the price of keywords relevant to holistic medicine (and, to be fair, nearly all medical topics). This increases the likelihood that drug ads will show up when readers seek information on healthcare alternatives.

We have seen this happen many times on our site.

For example, an online reader searching Google for information about “probiotics after antibiotics” will likely find her way to HPC’s article on this topic. But the ad adjacent to that article could be an ad for an anti-inflammatory drug for Crohn’s Disease—unless we specifically block it.

Google does allow online publishers to reject unwanted ads. But this obliges us to monitor our content and the associated ads constantly, and then track down the source of each undesired ad. It is a game of whack-a-mole, because the drug companies can easily create new domain names that seem unrelated and independent, through which they then bid on ad words and deploy their ads.

There’s nothing stopping a supplement company from paying for ads keyed to conventional diagnoses and hoping that its ads will appear instead of a drug company’s. But given the typical marketing budgets in pharma versus nutraceutical, the odds are against it.

In lumping supplements and pharmaceuticals together, Google is out of step with the Dietary Supplements Health Education Act (DSHEA), a federal statute that clearly delineates between supplements and drugs. Google is not obliged by law to comply with DSHEA, so there’s nothing illegal about its category smudge. But it is definitely not in alignment with the intent of DSHEA or the FDA’s enforcement of it.

Multiple Motives

If Google is deliberately mediating access to medical information, what are the company’s motives? We’ll never really know.

But there are several theories circulating among those of us concerned about and affected by the changes. None can be definitively proven, and no one possibility excludes the others.

- The “Appearance of Virtue” theory: Google—like Facebook and other massive online conglomerates– is under heavy scrutiny from the federal government, as well as governments outside the US, for its role in perpetuating fake news and manipulative political ads. The company is looking for ways to appear virtuous.

Clamping down on ‘fraudulent” medical information would be a quick way to placate the company’s scrutinizers by positioning Google as a protector of public health. Making a few algorithm changes that squelch information about non-conventional medical alternatives is an easy way to accomplish that goal.

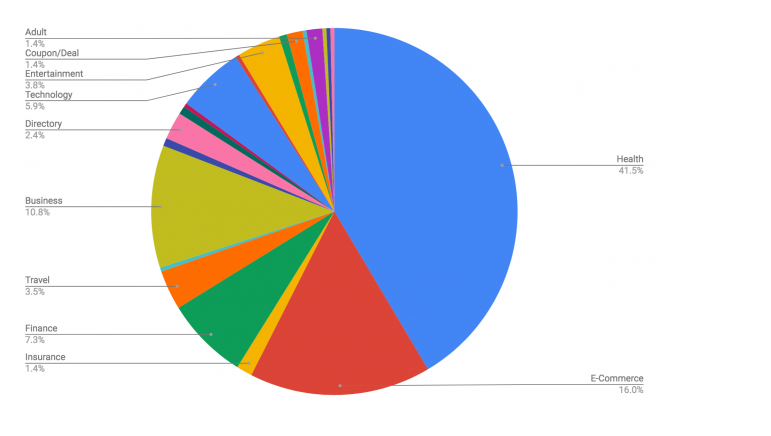

- The “Ad Revenue Maximization” theory: As we’ve already noted, Google makes heaps of money from its AdWords and AdSense systems. Pharma is one of the strongest performing categories in Google’s ad universe.

Proponents of this explanation argue that Google would have incentive to shunt traffic toward sites carrying pharma ads and pharma-friendly content, and away from sites that carry less lucrative natural products ads and content that promotes non-pharma alternatives.

- The “Suppression of Vaccine Dissent” theory: Many—though definitely not all—of the websites hit by the Medic 2 update are well known for their criticism of vaccines. Mercola.com, GreenMedInfo.com, and Kellybroganmd.com have been particularly vociferous in challenging conventional vaccine wisdom.

That, coupled with the fact that Alphabet, Google’s parent company, has invested heavily in partnerships with pharmaceutical and biotech ventures—including a flu shot company called Vaccitech—has led many observers to conclude that Google’s main motive is suppression of vaccine dissent.

All three theories are plausible, and all have holes.

Regarding the vaccine suppression issue, while it is true that some affected websites have prominent “anti-vax” stances, others do not.

Our Holisticprimarycare.net site has very little content about vaccines, and our coverage has been cautious, balanced, and nuanced. While we do believe it is possible that some vaccines may harm some people, and that vaccines are not 100% risk-free, we have never been categorically “anti-vax.” Yet we experienced the same magnitude of lost traffic as did sites that are outspoken in their vaccine criticism.

Regarding the AdSense theory, we’ll never know for sure if Google is deliberately trying to drive traffic toward pharma ads and pharma-friendly content. But it is certainly possible.

Whatever Google’s specific motives may be, there’s no question that the company’s algorithm changes, its manual penalties, and its AdWord policies have profound influence over the flow of healthcare information. This is already affecting everyone who works in the healthcare field—whether we realize it or not.

Beneath the surface of these issues lies a tense conflict between three foundational American principles: freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom to conduct business as a business sees fit.

The Constitution guarantees freedom of the press, and free speech in public places. But Google is not a public place, though it may feel like one to those of us who use it every day.

There’s nothing in any law that compels an information provider to make available any and all information that anyone desires to publish. Nor does the Constitution oblige content providers to present all information with equal prominence.

A bookstore owner is free to choose what types of books he or she sells. The same logic applies to Google as a private sector platform for information exchange. As such, Google has the right to determine how it wishes to conduct its business and what sort of information it serves up. This includes the right to censor content the company deems problematic.

Alternatives to Google

But we as business leaders, practitioners, and health information seekers also have rights and choices. Google may the dominant search engine, but it is not the only one.

Like many others affected by the algorithm changes, we at Holistic Primary Care are implementing strategies to restore our traffic. A big part of that has been to ‘de-Googlize” our business as much as possible by indexing our content on other search engines. There are many.

Our site is now indexed on Bing, Yahoo, DuckDuckGo, Ecosia, ASR, EntireWeb, and more than a dozen others. This takes time and effort, but it does work. Over the last three months, we’ve regained roughly 20% of our lost traffic. Almost all of this is new organic traffic from these alternative search engines.

We are also very fortunate in that the nucleus of our publishing business is, and has always been, our quarterly print magazine. Print is one medium over which Google has no jurisdiction.

That said, we know Google will dominate the internet for years if not decades to come. And Alphabet, Google’s parent, is rapidly positioning itself as a major player in healthcare. It recently acquired FitBit, the popular wearable health tracking company for a cool $2.1 billion.

Alphabet also entered into a partnership with Ascension Health, the world’s largest Catholic hospital and clinic network. The joint venture, called Project Nightingale, gives Google detailed personal medical data—health histories, lab results, diagnostic images, the works– from as many as 50 million patients.

Already, 10 million patient files have been transferred—a move that drew a lot of flack because the data was not anonymized, and because the transfer was not disclosed to either the patients or their practitioners before Ascension and Google went forward. Patients never had an opportunity to opt in or out. Most found out about it when the Wall Street Journal reported on it in early November.

Nightingale gives Google a massive medical database to feed its emerging artificial intelligence and machine learning systems. The company states that its ultimate goal is to improve quality of care by bringing greater intelligence to medical decision-making and better interoperability between hospitals. In all likelihood, the company will also mine Ascension’s database for information of interest to pharma, biotech, diagnostic, and device companies, and to further refine Google’s ad targeting.

As Google gets more directly involved in the actual practice of medicine, its role mediating the flow of health information will continue to raise profound questions without easy answers.

END