“It’s nice to find people who are still interested in my case,” says former au pair Edna Valenzuela.

The saga of this young Colombian woman, who was diagnosed with lymphoma while working for a Washington, DC, family, and almost deported in the midst of chemotherapy, throws much-needed light on the plight of a very vulnerable population.

The saga of this young Colombian woman, who was diagnosed with lymphoma while working for a Washington, DC, family, and almost deported in the midst of chemotherapy, throws much-needed light on the plight of a very vulnerable population.

Tens of thousands of young women from all over the globe work as au pairs in the US, providing much needed support for harried families struggling to keep all their proverbial balls in the air. But as Valenzeula’s case reveals, the au pairs themselves often have little support. When they get sick, their situations can quickly turn dire.

Their inherent vulnerability is amplified even further by the Trump administration’s harsh stance on immigration and uncertainty about the future for young, often uneducated, low-wage domestic workers with temporary immigration status.

Get Sick? Go Home!

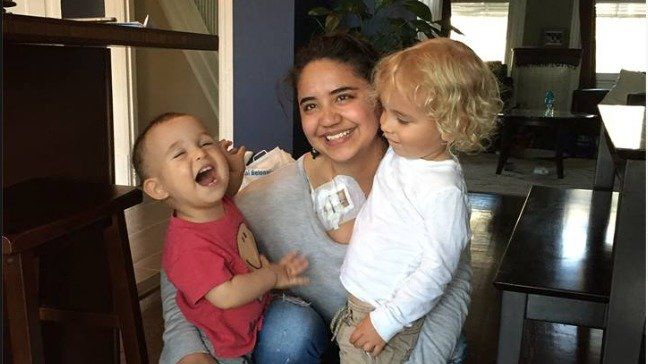

Edna Valenzuela’s case came to our attention last May, thanks to a petition posted on the change.org website by the family for whom she worked. The then 26-year-old, beloved for her “warmth, good humor and sharp mind,” was well into her contract with Mark and Shaina Aber-Hanson and their infant son, Jasper, when she developed what seemed to be a nagging cough.

After repeated urgent care and physician visits and several misdiagnoses—“allergies,” “bronchial infections”—the problem turned out to be a large mediastinal B-cell lymphoma that was putting pressure on the young woman’s heart and lungs.

Valenzuela was lucky. She was ultimately treated successfully and cost-free with a combination of surgery and chemotherapy through participation in a trial sponsored by National Institutes of Health.

At this time last year, however, a positive outcome was anything but certain.

When Valenzuela’s agency, AuPairCare, was notified of her illness, they abruptly terminated her contract. Rather than assisting her in acquiring an extension on her original J-1 visa which would allow her to remain with the Hansons and complete treatment in the US, AuPairCare pushed her to head back to Colombia.

Valenzuela says that at the time, this seemed like a death sentence. If sent home, she would have no employment or health insurance upon arrival, and no conceivable way to receive treatment for her cancer.

The situation was deeply unsettling for the Hansons, as well. They had grown quite fond of Edna and considered her a family member. In their change.org campaign, they note that they felt blind-sided by AuPairCare’s push to send Edna back to Columbia. “They have displayed absolute callous disregard for Edna and my family in this process.

Edna eventually did obtain a special B2 visa for medical treatment. At the time of this report, the lymphoma was in remission and she was still living with her host family in the US. She has the ability to extend her stay for medical care if the cancer returns. Fortunately, she has strong support from her US hosts who describe her as a “loving and superb” caregiver who “integrated so seamlessly into our family.”

The situation faced by Edna Valenzuela and her host family, while extreme, is not uncommon.

Out of 16 agencies that bring au pairs to the United States, very few offer effective health insurance or support when au pairs get sick or have medical emergencies.

Making as little as $4.35 an hour, au pairs typically cannot even come close to covering the fees involved in any medical crisis. Since they are temporary workers and not citizens, they do not qualify for Medicaid or any other government-funded medical coverage. On their small stipends, they certainly cannot afford private individual health insurance.

No Safety Net

When medical situations do arise, the placement agencies usually suggest host families simply send the unfortunate workers back to their home countries. These agencies charge substantial fees to the host families–the Hansons report that they paid AuPairCare more than $8,000 for Edna Valenzuela’s original year-long placement. But those fees would not go too far if the agencies were required to provide full-scale health insurance at market rates.

back to their home countries. These agencies charge substantial fees to the host families–the Hansons report that they paid AuPairCare more than $8,000 for Edna Valenzuela’s original year-long placement. But those fees would not go too far if the agencies were required to provide full-scale health insurance at market rates.

Au pairs are predominantly female and between the ages of 18-26 years old. According to the US Department of State, over 17,000 au pairs worked in the US in 2015 with DC, Virginia, and Maryland being the top three areas utilizing their services. Those numbers are likely an underestimate.

Au pairs work a maximum of 45 hours per week and are required to take 6 semester hours of post-secondary courses—typically paid for by the host families. Their work consists solely of childcare and they are not required to perform household duties. Host families provide a weekly stipend of $195, amounting to a little less than $10,000 per year. Au pairs are also given one weekend off per month, and sometimes two weeks of paid vacation time.

Au Pairs vs Nannies

Let’s compare this to the situation of an American nanny working in Maryland or Virginia.

The most glaring difference is the pay scale. Au pairs make well under the $7.25 to $8.75 minimum wage levels typical in Virgina and Maryland. A local nanny reported that she makes $18 an hour and that the average pay rate for the DC-Baltimore Metro area is between $10-18 per hour.

Not that American-born nannies have it easy. But without a language barrier and the risk of being sent home, they have a somewhat stronger position, and have the ability to demand higher workplace standards.

Many au pairs have never left their home countries before taking caregiver positions in the US. Trying to assimilate culturally while appeasing employers often creates tense conditions. In some cases, au pairs do not report abuse or misconduct for fear they will be sent home.

Nannies generally do not live with the families for whom they work, and usually have independent lives of their own. Au pairs are almost completely dependent on their host families. They must adapt to not only new cultures, but also to individual family dynamics. In the best cases—like Edna Valenzuela’s–they can become beloved quasi-family members. In the worst cases, they easily become victims of abuse with little social support or legal recourse.

These issues are not exclusive to the US. In Austria, a young au pair was forced to cook and clean for an entire family as well as work more hours than agreed upon. She never reported the family, said to be one of the wealthiest in their city, for fear of losing the income that she sent home to Vietnam.

Imagine being young, alone, and trying to fit into a new role in an unfamiliar world. Then imagine an accident—say a broken ankle—that leaves you unable to work. You must find a way to pay for medical costs out of your meager weekly wages. And then you realize that your employment can be terminated abruptly and very likely, you’ll be sent home with no job, and possibly no access to the sort of medical care you may have received in your temporary host country.

That’s the reality faced by thousands of young women working as au pairs all over the globe.

Passing the Medical Buck

According to numerous comments on AuPairMom.com, a popular forum for host families, when au pairs sustain injuries and/or illness, most are not at all familiar with how insurance companies and hospitals operate in the US.

Frequently, they go to emergency rooms. They often allow extensive lab tests to be ordered, assuming that all costs will somehow be covered through insurance, or through some type of state-funded system as are common in most countries outside the US.

Several au pair placement agencies suggest that families should thoroughly discuss healthcare issues and work out clear agreements prior to beginning any engagement, to reduce costly surprises for both parties. Agencies also suggest that au pairs purchase travel insurance that covers anything from basic needs all the way up to emergency surgery. The coverage and costs of these plans vary depending on what specific plans are being promoted by the agencies.

While some agencies like AuPairCare provide some level of insurance within a package deal, others like Au Pair World just make a suggestion that au pairs purchase their own insurance but leave it up to them to figure it all out.

Some agencies suggest that au pair healthcare is really the host family’s responsibility, and urge families help to financially support their au pairs if they become ill and unable to work.

In practice, this patchwork approach means that there are a lot of gaping holes in the healthcare safety net for au pairs here and abroad.

Pay a Lot, Earn a Little

Consider for a moment the costs put up by an au pair just to get to the United States. Application fees and processing can run anywhere from $225-2,500; J-1 visas are $160; airfares can be anywhere from several hundred to several thousand dollars, depending on the point of origin. Insurance add-ons of the sort proposed by placement agencies, are in the range of $1,400-1,600.

Au pairs pay all this, and sometimes more for the opportunity to work at a full time job (often more than full-time) paying them approximately $10,000 per year. While that may be more than they could make in their home countries, it leaves them extremely vulnerable economically. Even a relatively minor medical incident can be a crisis.

For people with a job title that literally translates from French as “on peer level,” au pairs are severely lacking in appropriate healthcare and support. And this raises an important question for the Americans who hire them: Why wouldn’t we want to do a better job caring for those caring for our children?

The agencies that place au pairs with US families promote the ideal that au pairs should be assimilated into their new American families. But who would ever imagine withholding essential health care from a family member?

Edna Valenzuela says she was lucky to have had such an accommodating host family as the Hansons. They allowed her and her mother to live with them while she was undergoing cancer treatment, even after her new visa required her not to work.

But for every case like Edna’s that works out well, there are likely dozens in which ill or injured au pairs are simply sent back from whence they came, and truly “lost to follow-up.”

Asked if her experience would prompt her to advise other young women against becoming au pairs, Edna Valenzuela is ambivalent. “I can’t say I won’t recommend the program,” she says, explaining that with the right host family, this is a wonderful opportunity for young people to experience other cultures and develop valuable skills.

But as her case so clearly illustrates, the typical au pair relationship here in the US leaves these workers extremely vulnerable. One injury or episode of illness can turn an otherwise enriching experience into a disaster. Would-be au pairs and the families that engage them need to enter into these contracts with their eyes wide open.

END