As health experts call for a major shift away from meat, the food industry has discovered "plant-based" living. US sales of plant-based meat and dairy alternatives topped $4.5 billion this year. But today’s vegan offerings — like the Impossible Burger or Good Catch’s finless "tuna"–raise questions about what counts as "natural." It takes a lot of processing to turn legumes into toothsome burgers, fish, and cheeses (Image: Svitlana Tereshchenko/Dreamstime)

Never before in human history has meat been so cheap and so ubiquitous in so many peoples’ diets.

So, it is ironic and perhaps inevitable, that at the height of mass scale animal agriculture, the food industry should embrace “plant-based” living.

Anyone who’s paying attention can attest that if 2018 was the Year of Hemp and CBD, 2019 will be remembered as the year of the Vegan. “Plant-based” restaurants, fast food chains, and grocery offerings are popping up everywhere. And they’re selling.

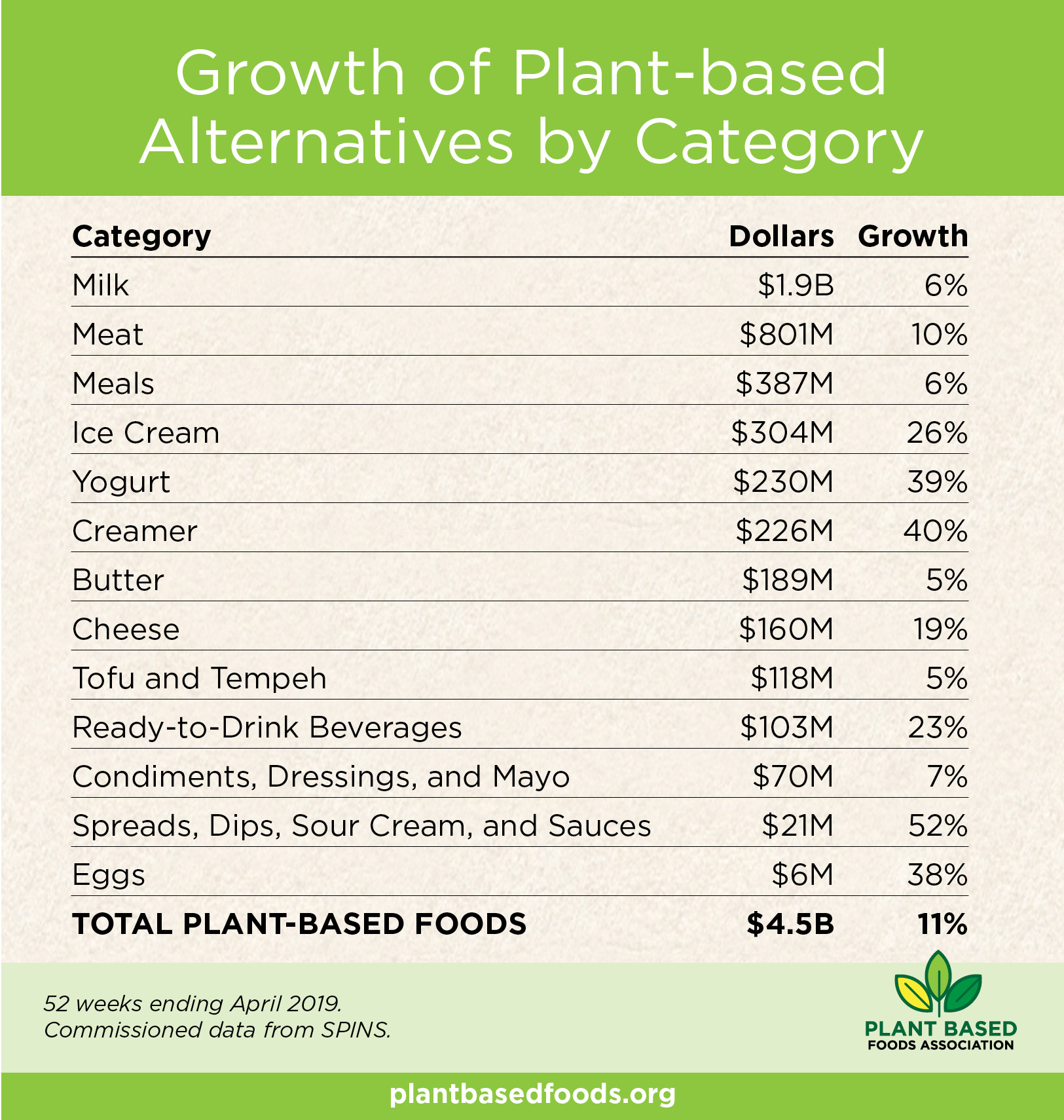

According to the Plant Based Foods Association and the Good Food Institute—two recently formed trade groups—US retail sales of plant-based foods topped $4.5 billion this year, growing by 11% in the last 12 months, and by 31% since April 2017. And that’s just meat and dairy substitutes, ready-to-drink beverages, condiments, and spreads. We’re not counting unprocessed fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains.

In contrast, total food retail sales grew by only 2% over the last year.

Meat Me at the Crossroads

Today’s “plant-based” phenomenon goes way beyond old-school tofu, kale, brown rice, and hummus. It’s all about high-tech tweaking of veg-based ingredients to make them look, taste, and feel like fish and flesh and fowl.

Sales of plant-based meats such as Beyond Meat and Impossible Burger are up 10%, and now represent 2% of all packaged meat sold in the US. Plant based yogurts—from nut or grain milks—have grown by 39%, while conventional mammalian yogurt sales are down by 3%. Vegan cheeses are up 19%.

Plant-based milk products are selling so well that dairy lobbyists are pushing for bans on use of the term “milk” for anything not derived from a mammal. And last year, the US Cattlemen’s Association had a big beef with plant-based flesh peddlers, filing a petition with the  US Department of Agriculture to prohibit use of the term “beef” and “meat” for any product “not derived directly from animals raised and slaughtered.”

US Department of Agriculture to prohibit use of the term “beef” and “meat” for any product “not derived directly from animals raised and slaughtered.”

France has already banned commercial use of the words “burger,” “steak,” “sausage” and “filet” for products derived from plants.

Meanwhile, major meat packers like Tyson Foods see the cruelty-free writing on the wall: last summer Tyson announced a major investment in Beyond Meat, a company that dazzled Wall Street last May when its stock value jumped by 163% one day after its Initial Public Offering.

And the world’s biggest burger joints are duking it out over the limited supply of Impossible Burger’s plant-derived yet toothsome patties. “It’s impossible for us to get the products now, because it’s all going to go to Burger King,” said former McDonald’s CEO and current Fatburger chairman Ed Rensi, in an interview with FoxBusiness.

Reinventing the Food Chain

There’s obviously nothing new about diets composed largely of plants. With few exceptions—Arctic dwelling Inuits, Maasai herders of the Great Rift Valley—that’s what most humans ate for millennia.

And vegetarianism as a cultural phenomenon is not exactly novel either. For centuries, prominent people—Pythagoras, Ben Franklin, Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, Mohandes Gandhi, Jane Goodall, Charlotte Bronte, Prince, and 3 out of the 4 Beatles to name but a few—have advocated plant-based living. Among Hindus and many Buddhists, it is the norm.

But there is something unprecedented about the mass-scale processing of legumes into substances that taste, smell, and chew like beef or tuna; the industrial development of vegan eggs; the transformation of nuts into ice cream and cheeses that satisfy connoisseurs.

The new plant-based “revolution” is an epic reinvention of the wheel…er, make that the food chain…that would be comical were it not so massive, lucrative, and beset by troubling questions. It is a curious confluence of health and environmental concerns, unfettered profit motive, and new food technologies that would have been unimaginable in Gandhi’s day.

The ebullience of the current market reflects the fact that many of today’s consumers—including many non-vegan omnivores—want more veg-based foods, but they want them to mimic animal products. In other words, they want to renounce their meat, and eat it too.

Food makers, restauranteurs, hotels, and fast food chains are happy to oblige. When Burger King started test-marketing Whoppers made with Impossible’s animal-free patties this year, it became obvious that “plant-based” is no longer a fringe phenomenon.

The new plant-based “revolution” is an epic reinvention of the wheel…er, make that the food chain…that would be comical were it not so massive, lucrative, and beset by troubling questions. It is a confluence of health and environmental concerns, unfettered profit motive, and new food technologies unimaginable in Gandhi’s day.

The plant-based movement has been deeply entwined with and influenced by holistic medicine for decades. These days, concepts and practices that were once ridiculed are being embraced by the medical mainstream.

You Are What Lancet EATs

“Food systems have the potential to nurture human health and support environmental sustainability; however, they are currently threatening both.”

You’d be forgiven if you thought those words were cribbed from the Whole Earth Catalog, that Back-to-the-Land bible of 50 years ago.

But they weren’t. They’re from The Lancet, earlier this year.

The venerable medical journal has formed a commission with the EAT Foundation—a European non-profit—to address, “the need to feed a growing global population a healthy diet while also defining sustainable food systems that will minimise damage to our planet.”

The EAT-Lancet Commission is comprised of 37 scientists and thought leaders from 16 countries who represent the fields of medicine, nutrition, agriculture, public policy, and environmental science. The group is led by Harvard’s Walter Willett, MD, a respected albeit controversial figure in the nutrition world.

The Commission’s report, Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems, is nothing short of a global mandate to replace meat and dairy with sustainably grown, plant-based alternatives. The project is wholly financed by philanthropic grants from the Wellcome Trust and the Stordalen Foundation.

It defines a universal healthy reference diet rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and unsaturated oils, with moderate amounts of fish, seafood and poultry, but largely free of red meat, processed meat, added sugar, refined grains, and starchy vegetables.

Widespread adoption of this ideal diet—and a retooling of food production to make it the norm worldwide—would simultaneously improve human health and attenuate environmental degradation, the commission contends.

“The human cost of our faulty food systems is that almost 1 billion people are hungry, and almost 2 billion people are eating too much of the wrong food,” write Lancet editors”— Tamara Lucas and Richard Horton, editors, The Lancet

They point out that while production of calories has more or less kept pace with global population growth, there are still more than 820 million people who have insufficient access to food. At the same time, many others drown in empty calories, saturated fat, meat, and refined carbs that predispose them to obesity, coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

“Unhealthy diets pose a greater risk of morbidity and mortality than does unsafe sex, and alcohol, drug, and tobacco use combined,” the EAT-Lancet team wrote.

The EAT-Lancet report posits that we now live in the “Anthropocene” era, in which humans and human activity are the predominant shapers of conditions on Earth. It’s a self-centered—some would say arrogant—perspective, but it is not without some truth.

Cuisine for the Anthropocene

Consider that the global population is currently about 7.7 billion, up from 2.6 billion in 1950; human agriculture now occupies nearly 40% of global land; food production accounts for up to 70% of all fresh water use; and conversion of wild lands for food production is the single biggest factor causing species extinction and loss of biodiversity.

The commission argues that phasing out animal-based foods would greatly reduce mankind’s impact on the world’s ecosystems while simultaneously reducing chronic disease.

“The human cost of our faulty food systems is that almost 1 billion people are hungry, and almost 2 billion people are eating too much of the wrong food,” write Lancet editors, Tamara Lucas and Richard Horton in a commentary on the EAT-Lancet manifesto.

In defining an ideal global diet, and outlining production and management principles that support it, the authors hope to create a common framework for “win-win” lifestyles (healthful and ecological) worldwide.

“Application of this framework to future projections of world development indicates that food systems can provide healthy diets (ie, reference diet) for an estimated global population of about 10 billion people by 2050 and remain within a safe operating space.” But only if massive numbers of people curb meat and dairy intake.

“Even small increases in consumption of red meat or dairy foods would make this goal difficult or impossible to achieve,” Willett and colleagues contend.

If you think the notion of a universal optimal diet smacks of “New World Order” logic, you’re not alone.

As Frédéric Leroy and Martin Cohen point out in a recent article in Sustainable Farming magazine, the new plant-based vision projected by groups like EAT-Lancet while laudable in intention, would end up consolidating ever more power and control in the hands of corporate agribusinesses to the detriment of small family farmers, ranchers, and fishermen who are already struggling.

Grand schemes like the one forwarded by EAT-Lancet will only increase the pressure on farmers to become, “providers of cheap raw materials to the food manufacturing industry as never before.”

Leroy, a professor of food science at Vrije Universiteit, Brussels, and Cohen, a social scientist who authored the popular book, I Think Therefore I Eat, are concerned about, “key figures from ever opportunistic global agribusiness, having discovered that vegan product lines are able to generate vast profit margins, adding value through the ultra-processing of cheap materials, such as protein extracts, starch, and oil.”

They caution against “dangerously simplistic” arguments that meat and dairy are categorically evil while all plant-based foods are inherently good, as well as “‘one-size-fits-all’ planetary solutions that overlook most of the ecological, physiological and cultural diversity.”

Ideals & Contradictions

Judging from the first annual Plant Based World Expo at New York City’s Javits Center in June, it seems that EAT-Lancet’s revolution has already begun.

With its goal of “activating a more rapid shift to plant-based living by bringing professionals and the community together,” the two-day  conference and trade show drew roughly 4,000 entrepreneurs, investors, healthcare practitioners, chefs, food service professionals, and veg-centric customers.

conference and trade show drew roughly 4,000 entrepreneurs, investors, healthcare practitioners, chefs, food service professionals, and veg-centric customers.

The three educational tracks—including one specifically for medical professionals—provided a forum for pioneers like Dean Ornish, T. Colin Campbell, Joel Kahn, Scott Stoll and many others to reflect on how the plant-based movement has evolved over the last 40 years, and where it’s headed (see Plant-Based Pioneers Have Their Moment and Untangling the Web of Food & Drug Addictions).

The exhibit hall spotlighted latest offerings from many of the veg-based heavy hitters—Daiya Foods, Miyoko’s Kitchen, Tofurky, Good Catch, Califia Farms among them—along with numerous smaller start-ups.

The event reflected both the idealism of the current market, as well as its peculiar paradoxes. Many of the products on display stretch the definition of “natural” to its break point.

The reality is, it takes a lot of “food science” to turn a six-legume blend into something that has the taste and texture of tuna, as Good Catch has done.

Founded by brothers Chad and Derek Sarno, both vegan chefs, Good Catch is making big waves in plant-based circles. They’ve figured out how to transform peas, lentils, chickpeas, soy, fava, and navy beans into something that approximates “the exact flakiness of tuna fish.” A DHA-rich algal oil supplies the briny flavor.

Though it probably won’t convince die-hard pescaterians, Good Catch’s “seafood without sacrifice” will appeal to people who’d like a tuna salad sandwich without the cruelty, the mercury, or the contribution to marine ecosystem collapse. And that’s a growing demographic segment.

Mission Impossible?

What happens when start-up vegan companies suddenly hit it big? It’s a phenomenon with which Impossible Burger is currently grappling.

Impossible Foods was founded in 2011 by Pat Brown, MD, PhD, a former pediatrician and Stanford biochem professor, who believes the biggest and most modifiable worldwide threat to global ecosystems is animal agriculture.

Backed by $365 million from Silicon Valley venture capitalists (including Bill Gates), Brown and his team set out to create a burger that sizzles, tastes, chews, and even bleeds like an ordinary burger, but without any animal ingredients. In large measure, they’ve succeeded.

Blinded taste tests indicate that many burger lovers cannot distinguish between an old fashioned beef patty, and Impossible’s soy-derived offerings.

The decisive factor seems to be the “blood.” Brown and colleagues figured out how to give their burgers the pinkness and succulence most other veg-based meats lack.

The secret is heme—soy-derived leghemoglobin to be exact.

Like animals, many plants produce their own forms of hemoglobin, and for the same purpose: to transport oxygen. Impossible initially began by extracting heme from the roots of soy plants. But this is very inefficient and not feasible for large-scale production. Today’s plant-based burgers sizzle, braise, and even "bleed" like beef, giving them broad public appeal. But they also contain genetically-modified ingredients, raising questions among some consumers. Image courtesy of Jamie Link Photography, for Plant Based World Expo

So, they turned to synthetic biology. The heme that puts the juice in Impossible’s patties comes from yeast into which the genes for soy hemoglobin have been inserted. In other words, there’s a GMO component to the formula—a fact not lost on some food advocates who see this as a stain on Impossible’s otherwise virtuous reputation.

Impossible’s business grew at a slow, steady pace for several years.Then, along came Burger King.

In May, the chain began selling Impossible Whoppers, with plans to introduce the pain-free patties in all of its 7,300 US restaurants by the end of the year. Simultaneously, retail and food service demand began to soar.

Impossible could not keep up.

The company no longer sells its signature pre-formed burgers in retail form, and has put all its resources into generating five-pound bricks for food service. According to a recent report by CNN, many of Impossible’s workers are now clocking 12-hour shifts and giving up weekends. Some office staff have volunteered to work in the factory to help increase output.

At the end of April, Impossible acknowledged the shortage and issued an apology to customers and small retailers negatively affected by it.

The company also admitted that the latest iteration of its product uses soy protein from genetically engineered crops. That’s not surprising, given that over 90% of all soy in the US is genetically modified to withstand heavy applications of glyphosate and other herbicides. The company claims it simply cannot meet the surging demand without using GM soy ingredients.

But the move has many food advocates crying foul.

The issue came to a head when Moms Across America (MMA) called out Impossible’s reliance on GMOs, tested the products for glyphosate, and found that it contained the herbicide at a level of 11.3 ppb (parts per billion). The group claims this is 11 times higher than that found in Beyond Meat’s pea-based burgers.

While the human health implications of glyphosate at 11.3 ppb are completely unknown, MMA contends that even at 0.1 ppb, glyphosate was shown to alter “over 4000 genes” in the livers and kidneys of rats.

Not surprisingly, Impossible Foods has rebutted MMA’s claims. The company contends that there is nothing wrong with the “responsible, constructive use of genetic engineering,” and that there is no scientific evidence whatsoever that low levels of glyphosate residue are dangerous.

Impossible dismisses MMA as, “an anti-GMO, anti-vaccine, anti-science, fundamentalist group that cynically peddles a toxic brew of medical misinformation and completely unregulated, untested, potentially toxic quack ‘supplements’.”

But many other groups, including Friends of the Earth, EcoWatch, the Organic Consumers Association, and representatives of the United Natural Products (UNPA) Alliance and Natural Grocers, have raised questions about the supposed health and environmental virtues of Impossible’s products.

In a comment following this year’s 80,000-strong Natural Products Expo West, UNPA’s communications director Frank Lampe said, “We’re disappointed that the company is using a ‘natural products’ show to promote its certainly not-natural product. The halo effect of being perceived as natural by its presence at the show…is a disingenuous move by Impossible Foods.”

Scale and Cost

The ability to scale to mass market volume while simultaneously adhering to ecological and “conscious capitalist” principles is a big challenge for the new wave of plant-based companies.

Another one is cost. These products are expensive.

Burger King’s Impossible Whopper costs $5.49, one dollar more per sandwich than the traditional beef option.

An 8-ounce two-pack of Beyond Meat’s uncooked burger patties costs $6.99 on FreshDirect. The same expenditure buys you 16 ounces of FreshDirect’s 100% grassfed local ground beef.

A 3.3-ounce packet of Good Catch’s skinless and finless plant-based tuna costs $4.99—which comes out to over $24 per pound. In contrast, a 5-ounce can of Bumble Bee is $2.19 ($7 per pound). FreshDirect sells raw yellowfin tuna steaks for $17.99 per pound.

A 6.5 ounce package of Miyoko’s Creamery Double Cream Chive vegan cheese is $9.99 ($24.64 per pound); a 7.5 ounce tub of Philadelphia whipped cream cheese with chives is $3.99.

At those price points, the EAT-Lancet commission’s worldwide veg revolution will be a long time coming.

But the cost equation could change dramatically as these companies grow, and the major agricultural conglomerates turn their attention to the burgeoning consumer demand. Economies of scale could bring product prices down considerably.

With that comes the danger that this entire movement, with all its values and visions for a healthier planet, will simply be commodified and turned into ever more junk food with a green veneer. Many would argue that this is already happening.

However these economic dynamics play out, the current plant-based movement makes it clear that food, health, and the environment are on peoples’ minds like never before. They’re eager for change, and many are willing to pay premium prices for it.

From a holistic medical perspective that is a very promising sign.

END