Ever wonder why the language describing dietary supplements always seems so vague, ambiguous, and…well…dodgy?

It’s because federal law requires it to be so.

But nearly 60% of healthcare professionals who routinely recommend or dispense dietary supplements in their practices do not really know or understand the law that governs the supplement industry.

If you happen to be one of them, here’s the nutshell: The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994 is the federal law that regulates and that, more or less, created the modern supplements industry. DSHEA established manufacturing and safety standards, determined the scope of allowable claims, and set strict limits on what supplement companies can—and cannot—say when marketing their products.

Enforcement of DSHEA—which is admittedly spotty–is jointly shared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

Enforcement of DSHEA—which is admittedly spotty–is jointly shared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

The FDA is supposed to ensure product safety, adherence to good manufacturing practices, and compliance with claims rulings. The FTC has jurisdiction over product advertising, and is charged with identifying and punishing fraudulent marketing.

DSHEA was revolutionary in its time. The law had massive consumer support, as well as bipartisan cooperation (remember, it was passed during an era when members of congress were still somewhat able to work together).

Prior to 1994, dietary supplements were not an officially recognized category of products. Vitamin companies were not permitted to make any sort of health claims about their products, and open advertising about them was more or less illegal. DSHEA changed that.

It’s common in medical circles to hear the oft-repeated refrain that “supplements are unregulated.” That is simply not true.

Dose vs “Serving Size”

Under the law, supplements are considered foods, and subject to the same rules and standards that govern food production. This explains why supplement labels indicate “serving size” rather than the more medical-sounding “dosage.”

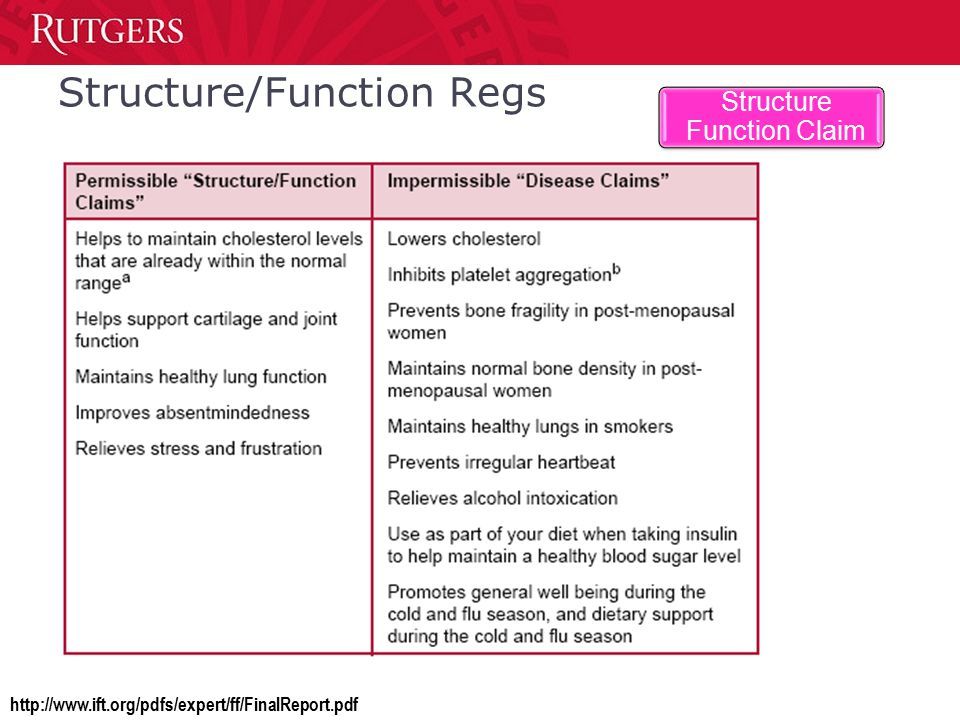

DSHEA explicitly prohibited supplement companies from making disease treatment claims—those are the exclusive province of pharmaceuticals.

But the law did create a new claim category—the Structure-Function claim–which allows supplement makers to promote their products as aids in supporting the health of particular physiological functions or anatomic structures, provided there is some scientific evidence to back the claim.

Hence, a company marketing a turmeric extract can state that the product be use to “supports healthy joint function,” but it cannot state that the compound can reduce inflammation—even if there’s clear science to prove that it does. Any claim that invokes disease terminology automatically renders the product a “drug” in the eyes of the regulators.

The other proviso is that the label must clearly display the disclaimer stating that the FDA has not evaluated the validity of the claim, and that the product is not intended to “diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease.”

DSHEA gave vitamin makers far greater marketing license than they’d had prior to its passage. But it also forced the industry into using the sort of ambiguous, wishy-washy marketing language that irks many medical professionals.

Simply put, the law prevents supplement companies from being specific about how their products can help your patients.

Medical Ignorance

“DSHEA” is a household term for anyone working within the supplement industry, but as Holistic Primary Care’s 2016 practitioner survey strongly indicates, it is unknown to a lot of clinicians—and this was a cohort of supplement-savvy practitioners.

We fielded the survey last March, and garnering responses from more than 850 practicing healthcare professionals, 31% of whom are conventionally-trained MDs and DOs. The majority self-identifies as “holistic,” “functional” or “integrative” in practice style, and 64% currently sell supplements in their practices.

Among those who do not dispense, 93% routinely recommend supplements.

The 44-item questionnaire included one question that asked, “What is your view on DSHEA?”

The acronym was deliberately not spelled out, because we wanted to find out to what extent this term—so widely used in industry—had currency in the clinical world.

Respondents could choose from among four answers: 1) DSHEA is fully adequate and effective; 2) DSHEA would be adequate and effective if properly enforced; DSHEA is inadequate and needs major revision; or 4) I do not know what DSHEA is.

The latter was by far the most commonly answer, chosen by 59% of the respondents.

Among the MDs in the cohort, 61% did not recognize the term “DSHEA.” The number was 69% among the DOs, and 65% among the nurses.

What was truly surprising is that this non-recognition extended to 58% of the chiropractors, and 43% of naturopaths. While those who dispense were more likely to recognize DSHEA than those who do not (48% vs 32%), it is a bit shocking that 52% of those who currently sell supplements in their practices do not recognize the name of the law.

Among those who do recognize DSHEA, only 6% consider it to be fully adequate and effective. Nineteen percent say the law is inadequate and needs significant revision. A nearly equal number, 18%, say DSHEA just needs better enforcement. But the largest proportion of respondents does not even recognize the term.

Deterring Research

“Who cares?” you ask. “Why do medical professionals need to know about some obscure law governing supplement companies?”

Because DSHEA affects what you (and your patients) learn about supplements.

The law also has a tremendous wet-blanket effect on clinical research. Large, high-quality studies are very expensive, and the law basically prohibits supplement makers from using any sort of disease-related data—however positive and well-validated—in their marketing campaigns.

Unlike pharma companies, which have very strong incentives to invest in research because they can use the data to make marketing claims, the supplement industry has very little incentive to invest in the sort of clinical research that the medical community demands.

Technically, supplement trials are not supposed to be disease-related at all—supplements by definition cannot treat diseases, remember? They’re supposed to prove that the product in question supports an already healthy biological structure or function. That, it should be obvious, is difficult to do.

There are plenty of holes in the current supplement regulations and there’s little doubt that ineffective, poorly made, sometimes contaminated products do end up on the market. These facts are not lost on our survey respondents.

Clinician Voices Needed

Verbatim responses indicated a high degree of concern about the proliferation of poor quality products, but these practitioners are equally wary of federal regulators. As one respondent put it, “There are too many low quality supplements on the market giving good ones a bad name. However, I am not sure I want government regulating supplements.”

Some view the FDA as a tool of Big Pharma—an industry that many physicians view with increasing skepticism and disdain.

“FDA always protect the big pharmaceutical industry and commonly disagree with natural remedies.”

The most promising signals came from the clinicians who lament the fact that practitioners are not involved in the regulatory process.

“Those who oversee the creation of this act are not well-versed in herbs, supplements etc, and therefore cannot pinpoint those who are qualified to dispense and advise. There needs to be an open dialogue on those of us who are qualified to advise and dispense.”

The fact is few practitioners participated in the drafting of DSHEA or the political efforts to push it through Congress. That absence was understandable—in 1994, few practitioners outside of naturopaths or chiropractors used things like vitamins and herbs as mainstay treatment options.

But times have changed in the 23 years since passage of DSHEA. Supplements are now part of healthcare. Many major medical centers—including the Cleveland Clinic, Duke and Scripps—now have high-profile integrative or functional medicine departments, where clinicians use nutraceuticals and herbs as adjuncts to or substitutions for drug therapies. Thousands more holistic and functional medicine practitioners are doing the same in smaller clinics.

Industry insiders believe that DSHEA will likely be revised or rewritten entirely at some point in the coming years. A series of regulatory moves by the FDA, FTC and the Drug Enforcement Agency last summer indicate that many in Washington want to change the status quo in ways that could limit availability and access to beneficial supplement products.

Nothing major is likely to happen in the immediate aftermath of the election, but there are plenty of people across the political spectrum who believe regulation of the supplement industry needs to change.

Holistically-minded clinicians, for whom supplements are important clinical tools, need to be part of the process that shapes these changes.

END