Many efforts to combat climate change prioritize the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. But cutting emissions is only part of the equation. To truly mitigate the harmful effects of carbon emissions, we need to look not at the skies, but at the dirt beneath our feet.

Many efforts to combat climate change prioritize the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. But cutting emissions is only part of the equation. To truly mitigate the harmful effects of carbon emissions, we need to look not at the skies, but at the dirt beneath our feet.

A number of environmental organizations as well as major multinational food corporations now recognize that the key to averting climate disaster lies in carbon sequestration: the natural process by which plants remove CO2 from the atmosphere and return it to the soil.

This may sound like an environmental science PhD thesis topic. But the concept, part and parcel of the emerging regenerative agriculture movement, has immediate practical applications. It is being taken seriously in corporate boardrooms.

In March 2019, for instance, food giant General Mills announced a commitment to advance regenerative agriculture practices on one million acres of farmland by the year 2030.

“As part of the food industry, we recognize that agriculture contributes to some of our most pressing sustainability challenges, and we believe that the most promising solutions start with healthy soil,” the company said in a press statement. “We are on a journey to bring soil back to life through regenerative agriculture practices, which protect and intentionally enhance natural resources and farming communities.”

To advance that journey, General Mills says it will partner with “organic and conventional farmers, suppliers and trusted farm advisors in key growing regions to drive the adoption of regenerative agriculture practices.”

Los Angeles-based nonprofit The Carbon Underground (TCU) has played a major role in promoting carbon sequestration to avert climate disaster. Founded in 2013, TCU is grounded in two fundamental principles:

1) There is no solution to climate change that does not include drawing down legacy carbon from the atmosphere.

2) There is no mechanism with the scale, ability, and immediacy to draw adequate amounts of carbon back down to mitigate climate change other than the restoration of soil and shift to regenerative agriculture.

“We were starting to hear about data on the relationship between soil and climate change that nobody had really looked at before,” says TCU president and co-founder  Larry Kopald, reflecting on the early days of the organization.

Larry Kopald, reflecting on the early days of the organization.

What the data showed was that healthy soil is capable of capturing significant amounts of carbon from the atmosphere. Land management practices that protect soil health not only strengthen its ability to sequester more carbon, they also improve other important environmental health markers like water quality and ecological biodiversity.

“We realized that if we can improve soil health at scale, we might be able to help reverse climate change,” Kopald told Holistic Primary Care. Today, his organization educates the general public as well as business, academic, and government sector representatives, about the power of healthy soil to restore a healthy climate.

Cutting greenhouse gas emissions is essential, but by itself, it will not get us where we need to be. Think of emissions reduction as turning off a fast-flowing faucet. Soil sequestration of carbon is like mopping up the floor.

“We will never solve climate change by reducing emissions” alone, Kopald said. “The only way we can fix the climate is to continue lowering emissions while also drawing legacy carbon back down from the atmosphere.”

Earth’s Biggest Carbon Sink

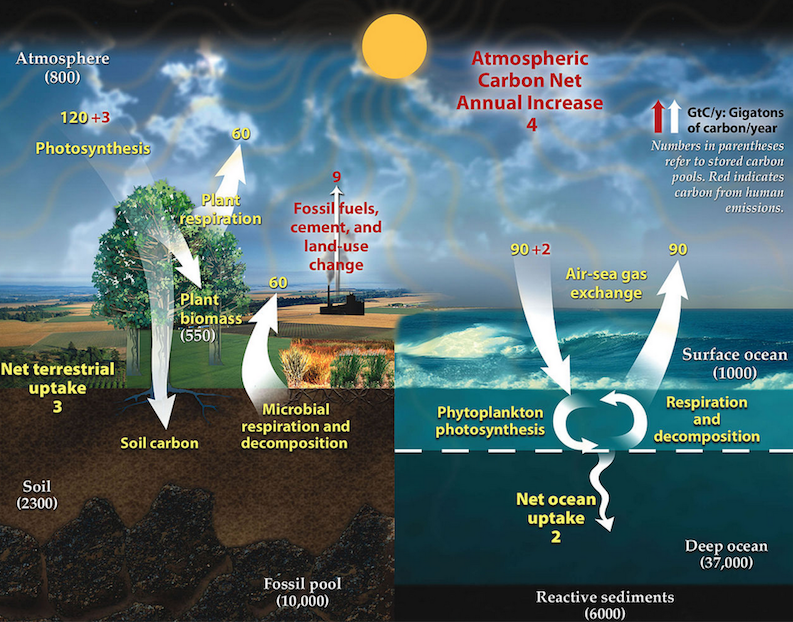

Global carbon cycling models indicate that the environmental impact of CO2 released from fossil fuel combustion will persist for thousands of years (Archer D, et al. Ann Rev Earth Plan Sci. 2009; 37: 117-134). That is because CO2 ––which accounts for around 80% of total GHG emissions in the US and 65% worldwide––has an extremely long atmospheric lifetime.

That said, several different natural processes remove excess CO2 from the atmosphere at varying rates, making it tough to pinpoint exactly how long it lingers. Much of the CO2 from fossil fuel combustion dissolves into the oceans relatively quickly—in geological terms, that is. Estimates suggest it takes somewhere between 20 to 200 years for ocean water to absorb a given amount of excess carbon from the air.

Chemical weathering and rock formation also draw down a portion of the atmospheric CO2––but that can take several hundreds of thousands of years. The reality is that CO2 released today will continue to affect the climate for decades to come.

Chemical weathering and rock formation also draw down a portion of the atmospheric CO2––but that can take several hundreds of thousands of years. The reality is that CO2 released today will continue to affect the climate for decades to come.

In the 1970s, when the issue of greenhouse gases first entered public consciousness, some environmental scientists–especially those working in the petroleum industry–argued that while it was true that burning fossil fuels does produce CO2, it won’t be a problem because the seas will absorb it all. Today, the general consensus is that the oceans cannot absorb carbon at a rate fast enough to prevent atmospheric warming. And beyond a certain level, carbon absorption is highly detrimental to marine ecosystems. Ocean acidification is a real and rapidly progressing problem, evidenced by massive die-offs of coral reefs worldwide.

The soil––and the plants that grow in it––are two of the Earth’s biggest carbon sinks. Trees and other plants pull CO2 from the air during photosynthesis, and carbon moves from plants (and the animals that eat them) back into the soil after they die and decompose.

The ground beneath our feet is a massive carbon storage system––but only if the soil is healthy. TCU estimates that one acre of land with good topsoil has the potential to draw down three tons of atmospheric carbon per year. One small family farm can pull more than 1,000 tons of carbon annually.

A single teaspoon of robust soil represents the greatest concentration of biomass anywhere on the planet. It contains more microorganisms than there are people on Earth. Billions of soil organisms spanning millions of species—from bacteria, fungi, and algae to microscopic insects, earthworms, beetles, ants, and mites– can all thrive in complex nested micro-ecosystems. Together, they help convert decaying organic matter into the rich, dark humus that characterizes healthy soil.

Restoring Degraded Soil

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN), over 33% of the Earth’s soils are already degraded and 90% could become degraded by 2050.

Many factors contribute to soil destruction, but industrial farming is a major culprit both in the US and globally.

In 2017, the agriculture sector accounted for nearly one tenth of all greenhouse gas emissions in the US. That is largely due to its heavy reliance on fuel-burning machinery. Farm equipment like tractors and irrigation pumps run on fossil fuels, as do many other large machines required to transport and process agricultural products.

Farm equipment like tractors and irrigation pumps run on fossil fuels, as do many other large machines required to transport and process agricultural products.

Beyond generating greenhouse gases, constant use of heavy farm machinery use also weakens soil quality. Constant plowing, tilling, and transportation across farmlands contribute to soil erosion, compaction, loss of soil structure, and nutrient degradation. In areas where croplands completely replace natural vegetation, exposed topsoil can dry out over time, creating inhospitable conditions for vital microorganisms that would otherwise occupy the soil and enhance its fertility.

To replenish depleted soil, conventional farms depend upon vast quantities of synthetic fertilizers, particularly nitrogen-based ones. The creation of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer is itself an extremely energy-intensive process fueled primarily by natural gas. Fossil fuel extraction, in other words, is necessary for the synthesis of chemical fertilizers. The two go hand in hand.

Further, nitrogen fertilizers emit greenhouse gases after they’re applied. This is because they stimulate soil microbes to convert nitrogen into nitrous oxide (N2O) at a faster-than-normal rate. N2O is a potent greenhouse gas, with around 300 times the heat-trapping capacity of CO2. Agriculture is the main source of anthropogenic N2O emissions.

The US Department of Agriculture’s National Organic Program prohibits the use of synthetic fertilizers on certified organic farms. While organic farming is on the rise in the US, the vast majority of our crops are grown on large-scale industrial farms dependent on fertilizers, pesticides, and heavy machinery.

Mother Nature is quite capable of creating fresh new soil––but she moves at a much slower speed than we humans do. It takes hundreds of years to generate just an inch of new top soil. Human activity is currently degrading the soil far too quickly for the Earth’s natural processes to keep pace. The FAO recently projected that present soil conditions will only support around 60 more years of crop harvests at our current levels of productivity.

Some have debated that timeline, but the general trend is clear: industrial agriculture as currently practiced takes a tremendous toll on the planet’s health.

Do No Harm to the Land

Data from a handful of new studies suggest that regenerative farming has massive potential to abate the harmful impacts of climate change.

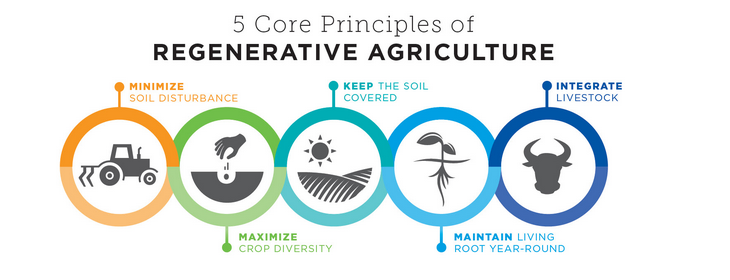

Regenerative farming refers to a system of holistic agricultural practices united by a core principle: do no harm to the land.

A host of different techniques fall under the regenerative ag umbrella; all aim to revitalize degraded soil and enhance biodiversity––and in so doing, to increase the Earth’s ability to sequester carbon.

Common regenerative practices include conservation tillage or “no-till” farming, in which a previous year’s crop residue is left on the soil surface rather than removed or tilled. This improves the soil’s ability to retain and infiltrate water, prevents erosion, and protects soil structure. It also provides a welcome home for the millions of soil microbes and insects that form a healthy soil microenvironment that would otherwise be displaced or destroyed in a tillage-based system. Minimal tilling also requires fewer tractor passes than conventional tilling, thus reducing a farm’s carbon footprint.

Crop rotation––growing a series of different crop varieties in one field over sequential seasons––is another important regenerative technique. Rotating crops replenishes the soil with diverse nutrients and discourages pathogens and pests from taking up residence. It’s a sharp contrast to industrial monocropping–standard practice in the world of Big Ag– in which the same type of plants is grown in the same area year after year.

Some regenerative farmers also integrate livestock into their soil restoration efforts. Using livestock to fertilize fields naturally with manure not only increases the soil’s organic matter, it also reduces the need for costly chemical fertilizer. Use of organic compost is another widespread practice on regenerative farms.

Some regenerative farmers also integrate livestock into their soil restoration efforts. Using livestock to fertilize fields naturally with manure not only increases the soil’s organic matter, it also reduces the need for costly chemical fertilizer. Use of organic compost is another widespread practice on regenerative farms.

Organic and regenerative agriculture share some common elements, but ultimately they are two distinct approaches to farming.

A certified organic farm must use natural alternatives in place of chemical fertilizers or pesticides and cannot utilize or grow genetically modified products. The majority of regenerative farms meet the qualifications for organic certification. But they go several steps further.

The term “regenerative agriculture” was coined in the 1980s by Robert Rodale, son of organic movement visionary J.I. Rodale, to distinguish a holistic kind of farming that encourages “continuous innovation and improvement of environmental, social, and economic measures.”

Soil health is the top priority in regenerative organic agriculture––but it’s not the only one. According to the Rodale Institute, “the idea is to create farm systems that work in harmony with nature to improve quality of life for every creature involved.” For regenerative farmers, that means not only promoting optimal soil health, but simultaneously maintaining high standards for the fair treatment of livestock as well as all workers involved with farm operations.

In 2018, the nonprofit Regenerative Organic Alliance launched a new Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC) pilot program for regenerative farms. Under it’s tagline, “Farm like the world depends on it,” the ROC certification takes the USDA Certified Organic standard (or its international equivalent) as a baseline, but builds upon it to include additional requirements for soil health and land management practices, animal welfare, and worker fairness.

Organic and regenerative farming both offer myriad environmental benefits, the potential for regenerative agriculture to mitigate climate change far outweighs organic-only practices, says TCU’s Kopald.

Organic and regenerative farming both offer myriad environmental benefits, the potential for regenerative agriculture to mitigate climate change far outweighs organic-only practices, says TCU’s Kopald.

“We are fans of organic farming––but to really scale up and change the climate and our food system, it has to be done through regenerative agriculture,” he argued.

But that’s going to take some doing. Taken together, organic farms account for just one percent of the world’s total agricultural land. Regenerative farms are an even smaller slice. In order to meaningfully address climate change via carbon sequestration, Kopald says, that number would need to jump to at least 25%.

Farming regeneratively could move the climate remediation dial further, faster, and on less land. Kopald cited a UN report indicating that based on the current rate at which farmers worldwide are adopting regenerative growing practices, 12% of farmland will be managed sustainably within the next 10 years.

The Top Food Trend

Regeneratively grown foods are still cropping up in grocery stores. Their popularity is already skyrocketing among seekers of natural, sustainable health food items.

Whole Foods, the self-proclaimed “healthiest grocery store” in America, predicts a substantial uptick in the number of consumers looking for food grown using regenerative practices. The company just released its annual list of top food trends for 2020, naming regenerative agriculture as the number one trend to watch.

Contemporary shoppers are increasingly interested in learning how production practices affect the environment, Whole Foods says. The chain expects to see more people shopping for brands that source regenerative ingredients in the coming year.

Partners in Business

That’s exactly the sort of movement that the Carbon Undergound’s founders want to see. “It takes a village to save a planet,” Kopald said. “We cannot solve the climate crisis alone.”

To that end, his organization fosters collaborations among governments, big business, and both small and large-scale farmers who see value in sustainable land management.

Some stakeholders measure that value in environmental or human health terms. For others, the benefits of regenerative agriculture reside in the potential profitability of new high-demand products. TCU’s leaders are uniquely poised to address both perspectives.

Kopald, a veteran communications and branding professional, previously worked for top advertising agencies. He’s managed ad campaigns for McDonald’s, American  Express and Honda. He’s helped launch multibillion brands including Acura, Oracle, and Huggies. He has also served on the boards of multiple environmental organizations like Oceana, the National Marine Sanctuaries, and 1% For The Planet, and has been involved with environmental communications for the UN and the International Olympic Committee.

Express and Honda. He’s helped launch multibillion brands including Acura, Oracle, and Huggies. He has also served on the boards of multiple environmental organizations like Oceana, the National Marine Sanctuaries, and 1% For The Planet, and has been involved with environmental communications for the UN and the International Olympic Committee.

Kopald’s co-founder, Tom Newmark, brings an intimate knowledge of the natural products industry to TCU. Newmark was the co-founder, president, and CEO of New Chapter, a popular dietary supplement company that he helped build into one of the premiere brands in the natural retail channel before selling the company to Procter & Gamble in 2012.

Newmark also served as board chair for multiple organizations including the American Botanical Council, and currently co-owns Finca Luna Nueva Lodge, an organic and biodynamic farm in Costa Rica that teaches regenerative agriculture.

“Our expertise is crafting campaigns that motivate people to act,” TCU says on its website. For TCU’s corporate partners, profit is a top motivator, Kopald says.

“What got us committed [to fighting climate change] was the realization that if big business will benefit, big business will support our efforts. If we improve soil health, not only will the food industry make more money, but we’ll have a healthier supply chain, too.”

Stalwart environmentalists might balk at the thought of cozying up to major corporations––but given the rate at which our planet’s health is deteriorating, Kopald says, we’re running out of time for idealism.

“Because of the urgency of climate change, we no longer have the luxury of being purists. Everybody has to be pulling their own weight,” he urged.

At TCU, “We understand the scale of supply chains and how to talk to C-level partners at corporations, in addition to those on the sustainability side,” Kopald added. “We see our role as helping to define the strategies for the movement, build alliances, and create opportunities for our partners to improve their business and make a difference at the same time.”

TCU also collaborates with government entities to further enhance soil health worldwide. The group recently received a request from the ministry of Thailand to help one of the country’s major agricultural producers convert its conventional fields into regenerative farms. TCU is now providing the Thai government with trainings on regenerative agriculture techniques for the nation’s 35 million farmers. It will also connect Thai producers with new US and international brands interested in purchasing regeneratively-produced ingredients.

TCU also collaborates with government entities to further enhance soil health worldwide. The group recently received a request from the ministry of Thailand to help one of the country’s major agricultural producers convert its conventional fields into regenerative farms. TCU is now providing the Thai government with trainings on regenerative agriculture techniques for the nation’s 35 million farmers. It will also connect Thai producers with new US and international brands interested in purchasing regeneratively-produced ingredients.

Since launching the collaboration with Thailand, Kopald says other international government and corporate entities––including supplement makers––have reached out to TCU for guidance around sourcing and producing regenerative food items.

Support Regenerative Farmers

TCU’s collaborative model reflects the critical importance of bringing diverse entities together to work across industry lines to effectively address the climate crisis.

At the personal level, though, many concerned citizens feel that their power to impact the climate crisis is frustratingly limited.

Kopald suggested a handful of steps individuals can take in their daily lives to promote soil health.

“One key is to support local farmers.” In an ideal world, those local farmers are also practicing regenerative agriculture––and even more ideally, using both regenerative and organic practices.

When shopping for food, Kopald recommended asking produce managers if any of the fruits or vegetables they sell are grown regeneratively. At restaurants, ask chefs if any of their menu items contain regenerative ingredients.

“The more that grocery stores and restaurant owners hear people asking about products grown regeneratively, the more receptive they will be to providing those types of products,” Kopald encouraged. “The products are already showing up, but we need to increase the demand.”

Individuals can also support soil health by utilizing or launching local projects like community gardens or urban farms.

For those who lack access to neighborhood garden plots or farms, TCU offers a unique program called Adopt-A-Meter. A $5 donation allows individuals to adopt one square meter of degraded soil in a region that TCU partners are working to restore. The funds go towards efforts like training farmers in regenerative growing techniques and purchasing composting equipment.

Most importantly, Kopald urged, whether we represent a business or personal interest, “we all have to wake up before it’s too late.”

“We’re not telling everyone they have to run out and buy electric cars,” he said. “All we have to do is change the way we grow our food––and prices go down, water quality improves, the planet gets healthier, and we get healthier.”

END