A new study reveals previously unidentified connections between the intestinal microbiome and markers of cardiovascular and mental health.

Bruce R. Stevens, PhD, Professor of physiology & functional genomics, medicine and psychiatry, University of Florida College of Medicine. Copyright Bruce R. Stevens, Ph.D.

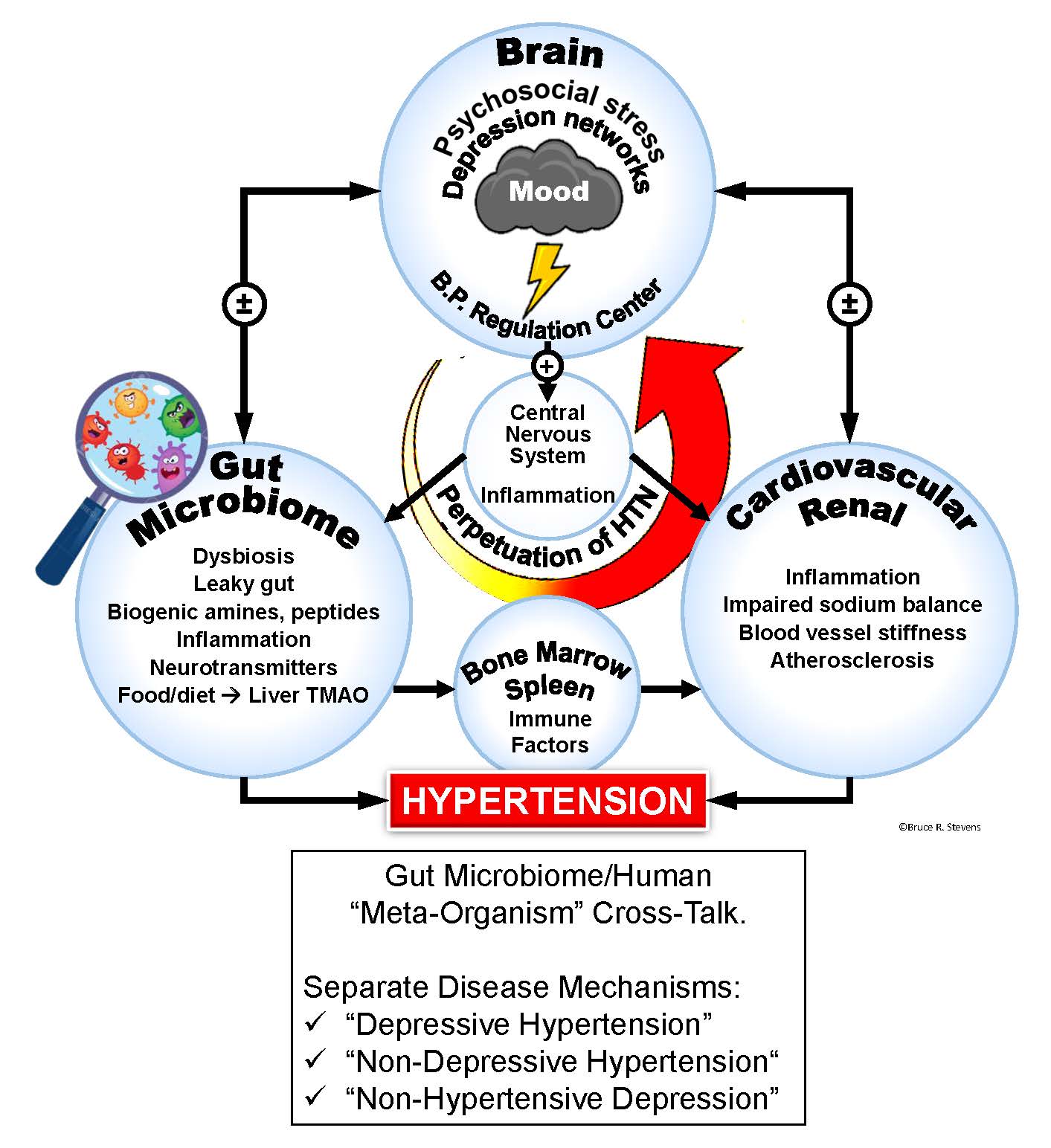

The data also underscore the important point that in many cases, hypertension and depression are inter-related and interactive conditions. They’re not separate and siloed disease “entities” that just so happen to co-occur.

New Forms of Hypertension

The study, led by Bruce R. Stevens, PhD, professor of physiology at the University of Florida College of Medicine, identified significant differences in the microbiomes of patients with high blood pressure, depression, and both disorders.

Stevens and his colleagues isolated bacterial DNA from stool samples of 105 volunteers. Sample analysis showed distinct groupings of bacterial genes and signature molecules in four different patient types: those with high blood pressure plus depression; those with high blood pressure but without depression; those with depression and normal blood pressure; and healthy subjects without either condition.

“We believe we have uncovered new forms of high blood pressure,” Stevens said of his team’s findings.

“Depressive-Hypertension,” the investigators’ term for high blood pressure with depression, “may be a completely different disease than ‘Non-Depressive-Hypertension’,” he proposed. Each of those conditions may in turn differ entirely from “Non-Hypertensive-Depression”–their term for people who have depression but healthy blood pressure.

Stevens presented his team’s top-line findings at the American Heart Association’s Hypertension 2019 Scientific Sessions in New Orleans.

Human Meta-Organisms

According to Stevens, there are several ways in which our gut microbes could contribute to the development of high blood pressure with or without depression.

“People are what I like to call ‘meta-organisms’––intertwined composites of human cells plus bacteria. Gut bacteria ecology interacts with our body’s physiology and brain, including steering disorders of high blood pressure and depression,” Stevens said.

“Certain gut bacteria release molecules into the bloodstream that result in hardened arteries and veins, or trigger bone marrow to start a whole-body inflammation firestorm that affects other organs. These unfavorable molecules can also cross the blood-brain barrier and inflame blood-pressure regulating centers in the brain, or modify mood centers with neural connections to blood pressure centers, or they can act indirectly through the kidneys.”–Bruce R. Stevens, PhD, Professor of Physiology, Florida State University

Scientists still aren’t sure exactly which vasoregulatory mechanisms might correlate with the various signalling molecules that gut bacteria produce. But mounting evidence indicates that the intestinal microbiota has a wide-ranging influence, not only on digestion, but also on our cardiovascular and nervous systems, metabolism, and hormones.

The Florida State University team has not yet released details on the specific microbial patterns they’ve discovered in connection with the various hypertensive and depressive states. When asked to comment, Dr. Stevens declined, presumably because the study has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

But he did share that, “Certain gut bacteria release molecules into the bloodstream that result in hardened arteries and veins, or trigger bone marrow to start a whole-body inflammation firestorm that affects other organs. These unfavorable molecules can also cross the blood-brain barrier and inflame blood-pressure regulating centers in the brain, or modify mood centers with neural connections to blood pressure centers, or they can act indirectly through the kidneys.”

While it is likely too early to make firm medical recommendations based on these early findings, American Heart Association (AHA) spokesperson Mary Ann Bauman, MD, believes they do offer an important clinical takeaway.

The message is, “for clinicians to once again be reminded that the bacteria in our gut are not just sitting there. They’re not just absorbing or helping us to break down food––they have multiple other functions.”

“We have to protect the gut microbiome––and that means not using antibiotics unless they’re absolutely necessary.” Bauman recommends following a general rule: “we don’t want to deplete the bacteria in the gut.”

Connecting the Dots

The University of Florida team believes gut microbiome analysis could eventually serve as a useful tool for identifying and treating different forms of hypertension and depression.

An illustration of the connection between the brain, central nervous system and other organs and how they interact with a person’s gut microbes to show different patterns of depression with or without hypertension. Copyright Bruce R. Stevens, PhD.

It is unclear why high blood pressure and depression are interrelated in some patients, yet unlinked in others. The question of how to accurately diagnose and treat the two conditions in their varying presentations has puzzled physicians, largely because they are trained to “deal with high blood pressure and depression as separate comorbid medical issues occurring in parallel,” Stevens argued.

He drew an analogy to another previously misunderstood medical condition: metabolic syndrome.

Years ago, metabolic syndrome was generally “viewed as a collection of independent comorbid disorders of obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance.”

Today, medical professionals recognize it as “a single unified disorder of inflammation involving whole-body pathophysiology encompassing interactions between insulin resistance and blood vessels hardened by disrupted lipid metabolism ultimately leading to high blood pressure,” Stevens said.

Prior to his group’s analysis, “no one had connected the dots to recognize that these may comprise a new unified syndrome which is not simply parallel comorbid symptoms.”

Rather than viewing high blood pressure and depression as separate conditions, Stevens says the study serves as a powerful reminder that the body exists in a “unified physiological state.”

Target the Gut, Help the Heart

He believes that the “uncloaking of these new medical categories opens future opportunities for doctors to better help patients by developing novel highly tailored treatment plans, especially serving previously treatment-resistant patients.” According to the AHA, nearly 20 percent of patients with high blood pressure do not respond well to anti-hypertensive drug treatment, even with multiple medications.

The University of Florida findings suggest that a number of factors including exposure to particular types of bacteria in certain geographical regions or during the birthing process ––can have an impact an individual’s risk of developing hypertension or depression. It is not simply a matter of genetic predispositions.

A healthy diet and lifestyle are important factors for engendering a cardiovascular-friendly gut microbiome.

“It is known that the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and Mediterranean diets high in fiber with omega-three oils, low in sugar, and low in red meat definitely benefit hypertension and depression by promoting a ‘good guy’ gut microbiome,” Stevens said.

Red meat contains carnitine and other compounds that “bad” bacteria convert into molecules detrimental to heart health. On the other hand, high-fiber, low-sugar prebiotic foods encourage the growth of “good” bacteria that strengthen gut integrity without prompting inflammation or molecular signals that could trigger high blood pressure and depression.

“No one had connected the dots to recognize that these (hypertension and depression) may comprise a new unified syndrome which is not simply parallel comorbid symptoms. The body exists in a unified physiological state.”

High omega-three fatty acid intake has been shown to squelch harmful gut flora, shifting the microbiome towards a more heart-healthy state while also mitigating mood disorders.

That said, Stevens emphasized, “for now, there is no silver bullet antibiotic or drug, and no scientific proof that any particular over-the-counter probiotic can treat these disorders. We are sorting this out, but it won’t be easy because of the millions of bacteria and the ecological relationship of those bacteria to each individual’s gut physiology.”

“What you can definitely do now is modify your diet to encourage the good-guy bacteria that won’t create inflammation or cause production of molecules that act on the blood vessels, kidneys, bone marrow, or brain to create high blood pressure and disrupt mood center circuitry,” he proposed.

Microbiome-Damaging Rx Drugs

Antihypertensive drugs, like most orally administered medications, can alter the composition and functioning of the intestinal microbiome. Similarly, certain antidepressants have surprisingly strong antimicrobial activity against beneficial gut bacteria.

NSAIDS, antacid proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, and chemotherapy agents can also be toxic to desirable gut bacteria. While their exact effects are not definitively understood yet, blood pressure beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and alpha-blockers also modify the intestinal microbiome.

“Our study discovered that a select subgroup of hypertension patients possess certain bacteria in their gut that possess metabolic interactions with their human hosts, making the bacteria susceptible such medicines,” Stevens said.

He speculated that one day, antibiotics could be isolated to specifically target the gut organisms linked to high blood pressure with or without depression.

“Members of our team have already begun experimental clinical trials repurposing the antibiotic, minocycline, to benefit treatment-resistant hypertension patients by way of their gut microbiome, and effects on inflammation of brain regions that control mood and blood pressure.”

Down the road, researchers may eventially identify specific probiotic strains that enhance gut microbiome strength and lessen the molecular triggers contributing to hypertension.

“Members of our team have already begun experimental clinical trials repurposing the antibiotic, minocycline, to benefit treatment-resistant hypertension patients by way of their gut microbiome, and effects on inflammation of brain regions that control mood and blood pressure.”

Bauman cautioned, however, that probiotics are best used as part of a larger holistic treatment approach. “I have nothing against probiotics and I recommend probiotics when people are on antibiotics,” she said. “But that is not the most natural way” to obtain beneficial gut flora or support intestinal health.

“We really need to be doing the things that our body craves, like eating fruits and vegetables and other whole foods,” she urged.

Regardless of the specific modality chosen, focusing on the gut appears to be a promising strategy for curbing cardiovascular as well as mental health risks.

“A primary significance of our unexpected discovery is the opening of new opportunities for healthcare provider teams to target your gastrointestinal tract in order to prevent, diagnose, and selectively treat entirely different medical types of high blood pressure and depression,” Stevens said.

“This is a revolutionary concept, because it means that in the future, patients could be diagnosed and treated for depression and/or hypertension with gastroenterologists on their healthcare teams,” he added. “And it reinforces the importance of nutrition in controlling and possibly preventing hypertension and depression.”

END