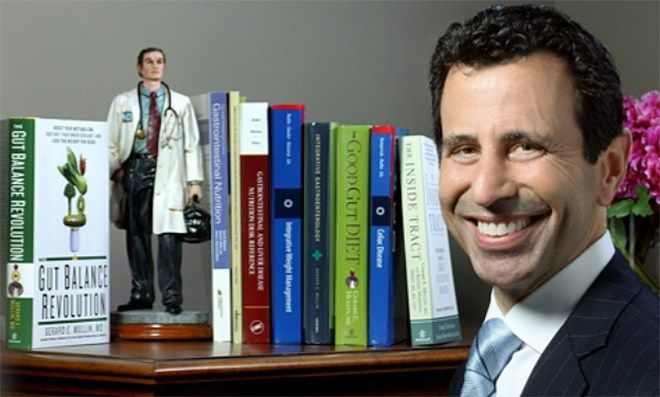

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) “is a very serious condition that needs aggressive intervention,” said Gerard Mullin, MD, MS, at the Institute for Functional Medicine’s recent 2018 Annual International Conference in Hollywood, Florida.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) “is a very serious condition that needs aggressive intervention,” said Gerard Mullin, MD, MS, at the Institute for Functional Medicine’s recent 2018 Annual International Conference in Hollywood, Florida.

While conventional medicine offers pharmaceutical solutions for symptom management, Mullin believes that to truly heal IBD, clinicians need to “DIGIN,” and work holistically to address the multiple facets of this condition.

Mullin’s DIGIN model looks at an IBD patient’s health status in five core areas: Digestion and absorption, Intestinal permeability, Gut microbiome, Inflammation and immune system, and Nervous system.

His perspective is shaped by his unique credentials: he’s board-certified in both internal medicine and gastroenterology, and also trained as a nutritionist. This enables him to draw from a wide range of lifestyle and dietary modifications, nutraceuticals, and botanicals to quell inflammation and restore balance in his IBD patients.

“Many patients end up on biologics and some other heavy medications, and a lot of their needs aren’t being addressed from a holistic, integrative perspective,” he told the IFM audience.

Dig In with Vitamin D & Butyrate

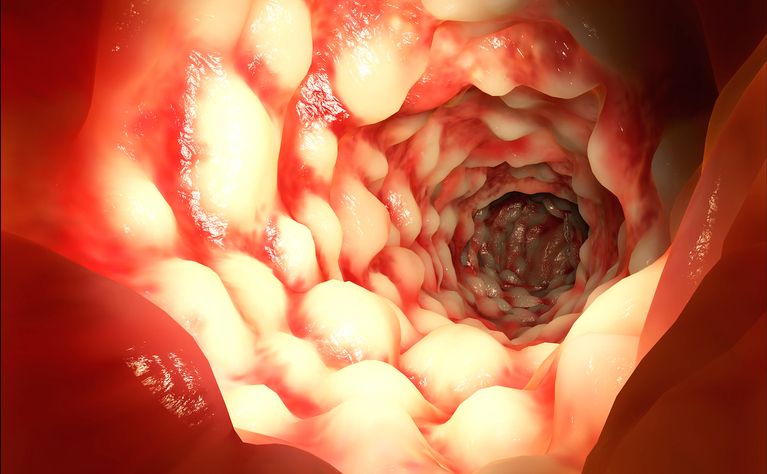

IBD is marked by ongoing inflammation in part or all of the digestive tract. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two main forms, together affecting around 1.6 million Americans. Because a myriad of factors contribute to Crohn’s and UC, treating these conditions can be very challenging, acknowledged Dr. Mullin, who is an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopins School of Medicine.

In any case involving digestive dysfunction, the crucial first step is to analyze the patient’s digestion and absorption capabilities. Malabsorption of essential nutrients like the fat-soluble vitamins A or D is very common in IBD patients. It is also wise to check vitamin D levels and supplement as needed. Typically, Dr. Mullin recommends more than 50 mcg (2000 IU) of Vitamin D per day, acknowledging that others believe higher doses closer to 100 mcg (4000 IU) daily are optimal.

The medical literature indicates variation in the doses that work best. The main thing, Mullin told his audience, is “we want to keep blood levels really robust and have a 25-hydroxyvitamin D of at least 50 nmol/L or greater.”

Mullin recommends stool analysis for bacterial metabolites like the short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate, an important substance produced by intestinal microbes when fermenting dietary fibers. Low stool butyrate levels are common in individuals with IBD. Butyrate serves a number of important roles, including maintenance of gut integrity, intestinal wall repair, immune system balance, and appetite regulation. Supporting healthy butyrate levels in the colon is necessary not just for IBD patients, but for everyone.

“If you do a CDSA [comprehensive digestive stool analysis] with IBD and you’re looking at a low butyrate, that is a prognostic indicator for a flare in patients with IBD.” Patients with IBD tend to exhibit an impaired use of SFCAs, which renders them even more susceptible to further intestinal damage. “You want to make sure you have sufficient butyrate available, whether in the diet or supplement form, for patients with IBD,” said Dr. Mullin, author of the popular books, The Good Gut Diet, and the Gut Balance Revolution.

“If you do a CDSA [comprehensive digestive stool analysis] with IBD and you’re looking at a low butyrate, that is a prognostic indicator for a flare in patients with IBD.” Patients with IBD tend to exhibit an impaired use of SFCAs, which renders them even more susceptible to further intestinal damage. “You want to make sure you have sufficient butyrate available, whether in the diet or supplement form, for patients with IBD,” said Dr. Mullin, author of the popular books, The Good Gut Diet, and the Gut Balance Revolution.

Check Zonulin Levels

The second aspect of the DIGIN model is intestinal health. Many IBD patients display increased intestinal permeability. Checking for leaky gut is key in all IBD patients. Zonulin testing is the primary method for identifying intestinal permeability. Zonulin modulates the tightness of junctions between the cells in the digestive tract wall. Functional medicine pioneer Alessio Fasano, MD, whose lab discovered zonulin, described the protein and its regulation of intestinal barrier function as “the biological door to inflammation.”

“When the finely tuned zonulin pathway is deregulated in genetically susceptible individuals, both intestinal and extraintestinal autoimmune, inflammatory, and neoplastic disorders can occur,” Fasano wrote (Fasano, A. Physiol Rev. 2011; 91(1): 151-75).

Mullin added that there are genetic components of IBD risk. Not only do Crohn’s patients often have leaky gut, he said, but their relatives are at higher risk for increased intestinal permeability too – even if they do not have the disease themselves.

Other elements like environmental triggers, immune responses, and the intestinal microbiota also influence the pathophysiology of IBD.

SIBO, SIFO & IBD

Examining the gut microbiome is the third step of Mullin’s protocol. “Harmony and balance starts in the gut,” he said, urging clinicians to assess patients for potential bacterial and fungal dysbiosis. Disruptions in healthy gut flora are widespread in people with IBD, so look for conditions like small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or small intestinal fungal overgrowth (SIFO). Elevated putrefactive SFCA levels also indicate gut dysbiosis, and point to low stomach acid, inadequate protein-digesting enzymes, poor protein absorption, or SIBO.

Microbiome testing can shed light on a patient’s distinctive physiology. For instance, in one patient with Crohn’s disease, Mullin found low counts of Akkermansia muciniphila, a bacterium that helps maintain healthy mucous layers, protecting the body against the invasive toxins. Low Akkermansia is a sign of mucin layer vulnerability.

maintain healthy mucous layers, protecting the body against the invasive toxins. Low Akkermansia is a sign of mucin layer vulnerability.

Like bacterial cultures, fungal cultures reveal critical details. “It’s surprising,” he noted, “because when we see lower biodiversity with bacteria, we think of that as being a bad sign for dysbiosis.” But when it comes to stool mycology, low diversity may be a good thing, while a greater richness and diversity of fungal species usually point to dysfunction in the gut.

There’s growing evidence that fungal infections like intestinal candidiasis influence some forms of IBD. An overgrowth of Candida albicans and other fungal species can even predict flares, especially in Crohn’s disease, Mullin said.

Biofilms offer important IBD clues as well. A biofilm forms when microorganisms attach to each other and to epithelial surfaces throughout the body. These sticky microbial communities exist “on our skin, in our respiratory lining, urogenital tract – they’re all over our body,” Mullin said. Generally they play regulatory roles in health, he explained, but “when pathogenic, they can actually turn on you and become part of the problem.”

A 2017 study found that Crohn’s patients tend to exhibit significantly higher levels of certain fungi and bacteria compared to their healthy family members. Further, these microorganisms “[work] together to form robust biofilms capable of exacerbating intestinal inflammation” (Hager, C. and Ghannoum, M. Dig Liv Dis. 2017; 49(11): 1171–1176).

Misprogrammed Immunity

The fourth arena of DIGIN is immune health. It is essential to assess immune function in IBD patients. The gut is in a constant “controlled state of inflammation” in healthy patients, Dr. Mullin explained. “You need inflammation in the gut,” he said. Health or illness depends on the degree to which the process is controlled.

On a daily basis, we’re presented with millions of antigens, and the immune cells need to be primed to react to the right things. The immune cells in the digestive tract – which make up an impressive 70-80% of the body’s total immune tissue – should know what is friend and what is foe. In IBD, though, “there is misprogramming,” causing the cells to “overreact to things they shouldn’t react to.”

A number of immune system biomarkers can help you get a handle on what’s happening with IBD patients. Immunoglobulin A (IgA), an antibody involved in immune exclusion, is a big one. IBD patients typically show elevated secretory IgA levels, suggesting an upregulated immune response. Other useful markers of inflammation include ferritin, albumin, and calprotectin.

Stress & Sympathetic Overload

Because IBD is considered a “digestive” disorder, most physicians tend to focus on what’s happening in the GI tract and often overlook the nervous system. This, says Mullin, is one of the biggest gaps in the care of these patients.

He recommends neurotransmitter testing, with special attention given to stress levels. “Stress through the sympathetic nervous system will increases the inflammatory response, especially in people with genetic and microbiome susceptibilities.” Poor sleep is another common symptom of IBD, so asking patients about sleep quality is important, too.

Mullin teaches patients mindfulness-based meditation as a stress reduction technique. Many other mind-body therapies, from acupuncture to gut-directed hypnotherapy, have been studied in the context of IBD. When practiced consistently, they can help greatly. For IBD patients, learning to “keep calm and put out the fire” raging in the gut can make all the difference in cooling inflammation.

The 5 Rs

After using the DIGIN model to assess his patients, Mullin follows the “5 R” program to restore good health: Remove, Replace, Reinoculate, Repair, and Re-balance.

Removing all known disease triggers – which often means offending foods – is imperative. This takes some commitment from patients. To heal from IBD, patients must learn to identify the antecedents to their digestive dysfunction, as well as any triggers that worsen it.

Conventionally-minded practitioners may argue that diet plays no role in IBD, but patient experience tells a different story. It’s imperative that IBD patients learn to see whole, healthy, natural foods as medicine.

Epidemiological data links diets high in animal protein (particularly red meats), refined sugars, and trans fats to increased IBD risk. Foods like these “can induce changes in the microbiome, which in turn can wreak havoc on the body – particularly if the immune system is genetically susceptible,” Mullin said.

The right diet can be a powerful tool for reducing systemic inflammation. But before we can use food as medicine, the first step is to cut out foods known to cause gastrointestinal discomfort, like caffeine, dairy, alcohol and sugar alcohols, and greasy, fried, spicy, or high-fat foods. This needs to be individualized, because not all IBD patients are affected by the same foods.

By simply removing foods likely to provoke allergic responses – dairy products, wheat, eggs, nuts, and citrus fruits – many IBD patients experience significant symptom relief. In his own research, Mullin has found that that patients with active Crohn’s who followed an elimination diet demonstrated an 18% higher probability of inducing remission than patients who received no intervention. Elimination diets are not a cure-all, but they are a useful adjunct for many with IBD.

The ultimate goal is to move away from the standard Western diet and more towards an anti-inflammatory, phytonutrient-rich, mainly plant-based diet.

IBD patients should also pay attention to other non-food substances – like medications – that promote digestive distress. NSAIDs, for instance, which many IBD patients use for pain relief, “are well known to be provocateurs for IBD” and can worsen leaky gut, Mullin said.

Minimize Antibiotics

Antibiotics contribute to long-term intestinal imbalances, too. Mullin urged great caution in the use of antibiotic drugs, describing a study showing that exposure to certain antibiotics during childhood is associated with an increased risk of IBD later in life. There’s a linear relationship between the number of antibiotic doses participants received as children and the incicence of IBD in adulthood. These data underscore the need to reduce all unneccessary use of antibiotics during childhood.

We now understand, Mullin explained, that in earliest years, and especially the first few months of life, a developing child’s immune system undergoes a critical training period that’s easily disrupted by high antibiotics use.

In many cases of gut dysbiosis, candidiasis, and SIBO, herbal alternatives to Rx antibiotics can be just as effective. Mullin co-authored a 2014 study comparing rifaximin, an antibiotic widely prescribed to treat SIBO, against two different herbal therapy combinations (Dysbiocide and FC Cidal or Candibactin-AR and Candibactin-BR) in SIBO treatment. He and his colleagues found that the herbal therapies were at least as effective as rifaximin in resolving SIBO. They also concluded that the herbal preparations appeared to be as equally effective as triple antibiotics for SIBO rescue therapy in patients nonresponsive to rifaximin treatment (Chedid, V. et al. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014; 3(3): 16–24).

In his practice, Mullin prescribes a low FODMAP (Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Mono-saccharides and Polyols) diet supplemented with herbal therapies to combat intestinal inflammation in patients with SIBO. He generally encourages IBD sufferers to reduce consumption of foods high in short-chain carbohydrates and boost their intake of low-FODMAP fruits, vegetables, and omega-3 fatty acids.

Restoring Healthy Flora

Step three is re-inoculation. A compromised gut requires replenishment with healthy flora, which is achievable in a variety of ways. Eating or supplementing with prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics – foods or supplements that combine both pre- and probiotics – is one effective way.

Prebiotics, which are fermented by friendly gut bacteria into SFCAs, tend to benefit patients with UC. Crohn’s patients, however, do not typically experience the same level of relief from prebiotics, largely because Crohn’s tends to involve the small bowel. Dr. Mullin reviewed research on two kinds of prebiotic fiber: fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and inulin. The former increases beneficial Bifidobacteria and decreases Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) scores. FOS and inulin both reduce calprotectin and improve symptoms in UC patients.

Numerous clinical trials have explored probiotics as an IBD treatment. While the literature is somewhat mixed for Crohn’s, studies do support probiotic supplementation for UC, particularly in moderately active cases. Treating acute flares with probiotics can even help place patients in remission, a “powerful message” clinicians can share with IBD patients, Mullin said.

In one study of patients with UC refractory to drug therapy, researchers found that taking a probiotic containing 3.6 trillion CFUs for six weeks induced remission when other conventional therapies did not (Bibiloni, R. et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005; 100(7): 1539-1546).

In really severe cases, clinicians might also consider “the ultimate probiotic” — a fecal transplant. There is some evidence that fecal transplantation benefits patients with acute, refractory UC.

Butyrate Enemas Quell Flares

Butyrate Enemas Quell Flares

Short-chain fatty acids also support a healthy gut microbiome. “SFCAs can help bail your patient out of a hot flare of UC if you give an enema with SCFAs of butyrate,” Mullin shared, adding that butyrate enemas can even help induce remission in some patients. SFCA enemas can also be used as salvage therapy in IBD patients who don’t respond to standard medical therapy. “You can actually save someone from either needing [the prescription medication] Remicade or surgery.”

To repair the damaged gut, Mullin uses several anti-inflammatory herbs, spices, nutraceuticals, and botanicals. His go-to’s include omega-3s, vitamin D, L-glutamine, boswellia, andrographis, wormwood, ginger, and concentrated immunoglobulin products like serum-derived bovine immunoglobulins. He prescribes curcuminoids liberally as well, proposing that “turmeric is a no-brainer to use for your patients — you want at least 2,000 mg a day.”

The final step of the 5 R program is to re-balance the gut, accomplished either by reducing excess pathogenic bacteria or replenishing friendly microbes.

To this end, Mullin uses specialized therapeutic drinks containing a mix of prebiotics, probiotics, and other ingredients like omega-3s and guar gum. He works with compounding pharmacies that make tailored products for his patients, noting that a quick internet search identifies pharmacies that are either local or will ship products.

When prescribing these medical drinks, “warn your patients — it does not smell nice. But in four to six weeks, they’ll love you, especially if you bail them out of trouble for acute UC and they’ve been refractory to steroids and medical therapy, and are discussing Remicade or surgery or fecal transplant.” The drinks can be consumed once a day, although Mullin usually prescribes them twice daily, both first thing in morning and at night before bed.

The plethora of strategies clinicians might employ in IBD cases also includes helminth therapy. An area of increasing interest among integrative practitioners, nematodes can regulate immunity, inducing a Th2 immune response in humans. These “purposeful parasites” can modulate the immune system in Chron’s patients, who tend towards Th1 dominance, bringing balance by inducing Th2 response.

Low-dose naltrexone, another emerging therapy, not only induces IBD remission, but promotes a number of favorable immune system effects.

Mullin stressed the paramount importance of a multi-pronged approach to IBD. “People don’t just take one supplement or do one thing for this kind of illness, particularly when it’s severe.” From that perspective, addressing IBD becomes a journey of discovery, determining which tools will best support individual patients throughout their healing process.

END