This flu season, practitioners have a new adjuvant-free option to offer people who’ve been reluctant to take conventional flu shots.

This flu season, practitioners have a new adjuvant-free option to offer people who’ve been reluctant to take conventional flu shots.

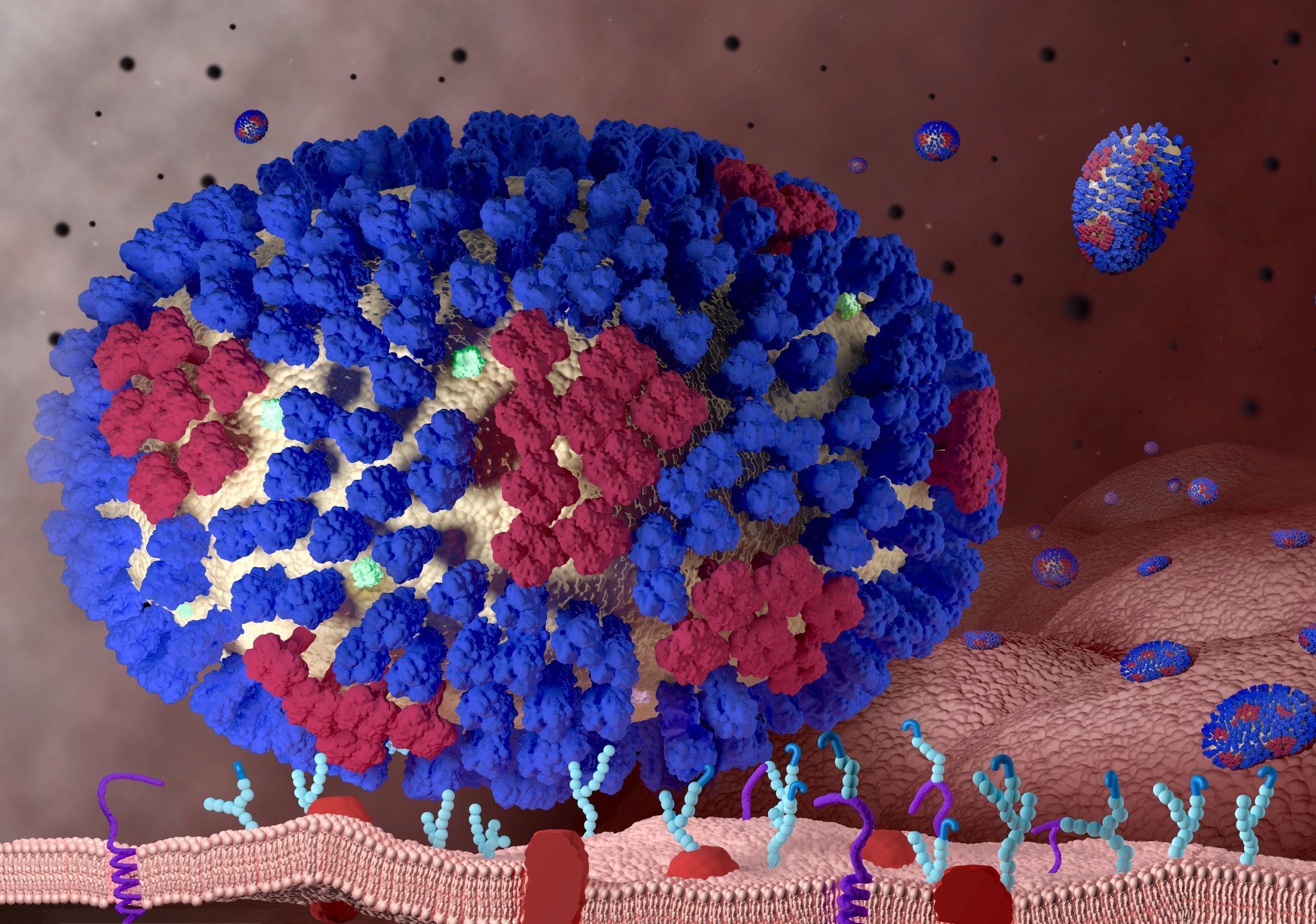

The new vaccine, called Flublok, delivers up to three times as much antigenic protein per dose as other flu shots, without additives like thimerosal or aluminum.

Produced using a recombinant DNA method, Flublok has another major advantage: it does not require incubation on chicken eggs. This greatly reduces the eco-footprint of the manufacturing process, and eliminates the risk of bacterial contamination or exposure to egg allergens.

Flublok received FDA licensure late last year for use in adults over age 18, with no upper age limit.

Protein Sciences, a small Connecticut-based biotech company that makes Flublok says the new vaccine is entirely free of heavy metals, formaldehyde, latex, antibiotics, gluten, and egg residues. The company’s recombinant method does not require use of actual live flu viruses, meaning that unlike other shots, it is free of attenuated viral particles.

Manon Cox, PhD, CEO of Protein Sciences, believes her company has obviated most if not all concerns people have about vaccines—concerns that have been loudly emphasized by vaccine critics and unduly dismissed by equally vociferous vaccine advocates.

In short, the new product is about as clean and green as a vaccine can get.

The genetic technology behind Flublok could be used to produce adjuvant-free versions of other vaccines, including some of the childhood shots that have been the focus of the so-called “vaccine wars.”

Short of Middle East politics and immigration reform, few issues generate as much social friction and self-righteous rancor as childhood immunization policy.

A new generation of adjuvant-free vaccines would reframe the debate by highlighting the distinction between people who accept the basic premise of vaccines but have concerns about potential toxins in the products, and those who are categorically opposed to all vaccination on a doctrinal level. It’s an important difference that’s gotten lost in all the polemics.

A Long Time Coming

An advance like Flublok should have happened 30 years ago, says Dr. Cox.

And it could have, but for the contradictory economic incentives that shape the Looking Glass world of vaccine development.

Vaccine innovation proceeds at a glacial pace for three basic reasons: Clinical trials needed to win FDA approval are large and very costly; Payors, whether federal or private, are reluctant to pay higher prices for innovative products—especially ones that need to be used widely; Pharma-sector investors have little taste for vaccine ventures.

Add the public’s rising mistrust of drug companies in general, and vaccine makers specifically, and you’ve got a recipe for stagnation. Companies have had little incentive to enter the “valley of death,” as Cox jokingly calls vaccine development.

“If I’m earning $2 billion a year, like Sanofi (maker of the Fluzone vaccine), using 70-year-old egg-based technology, why would I want to invest in anything new?”

egg-based technology, why would I want to invest in anything new?”

She said Protein Sciences has been working on Flublok for the better part of 20 years, at a total investment approaching $1 billion.

Until Flublok, all flu vaccines were variations on a very old fugue:

- Each February, World Health Organization experts publish a consensus on what they think will be the predominant flu strains in the next season;

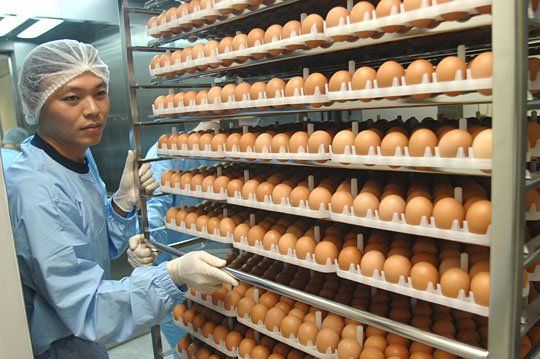

- Based on these predictions, vaccine-makers select viruses to be inoculated into 11-12 day-old embryonated eggs;

- The eggs are incubated for 48 hours, then opened, and virus-laden allantoic fluid is extracted;

- The fluid is treated with chemicals like beta propiolactone or formalin to kill or inactivate the viruses;

- The attenuated viruses or antigenic proteins from them are combined with adjuvants to enhance the antigenic effect, antibiotics to counter potential bacterial contaminants, and other additives.

This combination of educated guesswork and early 20th-century microbiology is slow, inefficient, and enormously wasteful, says Dr. Cox.

The Smell of Burning Eggs

It takes as many as three eggs to produce a single dose of a flu shot. High-dose versions require more. To make an annual stockpile of 150 million doses, drugmakers burn through as many as 500 million eggs.

“I sometimes joke that Bird Flu is the revenge of the chickens against us for taking so many of their eggs,” said Dr. Cox.

“I sometimes joke that Bird Flu is the revenge of the chickens against us for taking so many of their eggs,” said Dr. Cox.

Conventional vaccine-making is a dirty process. “The endotoxin loads with egg-based vaccines are far greater than in a recombinant protein vaccine. That’s one reason they need to add antibiotics,” she said. Bacterial endotoxins in vaccines can trigger flu-like syndromes or other more dangerous reactions, which are sometimes attributed to the vaccine itself.