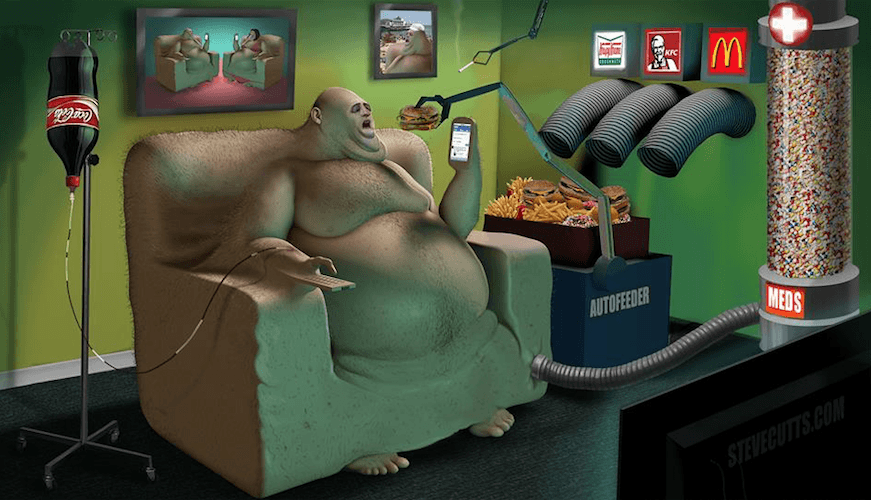

Big Food companies have spent billions of dollars manipulating nutrition science and food policy for their own gain, especially to the detriment of poor, less educated consumers. And it’s affecting the nation’s health.

Big Food companies have spent billions of dollars manipulating nutrition science and food policy for their own gain, especially to the detriment of poor, less educated consumers. And it’s affecting the nation’s health.

But how can we spot food industry agendas when they hide out in front groups with seemingly charitable missions and benign-sounding names like the Alliance for Food and Farming or Protect the Harvest? How can we call them out when they also spend millions of dollars supporting “healthy” activities like youth soccer and baseball in poor communities?

Mark Hyman, MD, believes the food and beverage industry has been plying publich opinion for decades by quietly infiltrating nutrition science, strong-arming federal food and nutrition policy, and strategically harnessing the media’s influence.

He unraveled what he sees as a tangled web of deceit during a provocative presentation at the 2019 Integrative Health Symposium in February.

Seedy Science, Pay-for-Policy

One of the biggest issues with nutrition research today, according to Dr. Hyman, is that the amount of funding coming from “industry sources” far exceeds that coming from government and independent sources. The difference is more than $10 billion per year — $12.4 billion from industry versus $1.5 billion from independent institutions.

Unfortunately, he said, most people are unaware of Big Food’s influence on academia.

“There is a lack of transparency in nutrition science. I was fooled by studies and entire organizations behind the science,” Hyman admitted. “The food industry has been flooding the literature for years in an effort to blunt negative studies on their own products. The companies behind sugar, soda, and processed foods have made a concerted effort to manipulate the data to make these things not look so bad.”

More than a decade ago, a paper in PLoS Medicine raised the issue of industry-funded nutrition studies, cautioning that this “may bias  conclusions in favor of sponsors’ products, with potentially significant implications for public health.”

conclusions in favor of sponsors’ products, with potentially significant implications for public health.”

Of the 206 studies reviewed in this paper, there were zero unfavorable conclusions from industry-funded studies, but 37% unfavorable conclusions in studies that were funded independent of industry sources. The industry-funded studies were almost eight times more likely to have a positive outcome than the independent studies.

Dr. Hyman, Director of the Cleveland Clinic Center for Functional Medicine and Board Chairman of the Institute for Functional Medicine, claims that while a journal like the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition is held up as the “gold standard” of peer-reviewed nutrition literature, the organization behind it — the American Society for Nutrition — is heavily funded by the food industry.

“It’s almost a joke, especially when it comes to defending things that are clearly unhealthy,” says Hyman.

Neither are the US Department of Agriculture’s Dietary Guidelines safe from food industry influence. In a compelling article published on the Medium website in 2016, author Zara Abrams points out that 10 of the 14 members of the Dietary Guidelines Committee had consulting arrangements or received funding from food industry organizations or corporations.

To address this issue, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a joint report in 2017 called Redesigning the Process for Establishing the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that put forth a new strategy for coming to consensus. It offers a comprehensive review, with recommendations for improving the rest of the process to update the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

But unless USDA embraces and implements the guidelines, the food industry’s financial resources will continue to have far greater impact than any expert position paper.

Soft Drinks, Hard Currency

For years, soda has been maligned for fueling the obesity epidemic, with strong data to back up this connection. But that’s not the story that industry-funded studies tell.

An August 2018 review article in the journal, Public Health Nutrition, exposed significant bias in research on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs). Of the 133 studies from 2001 to 2013, 82% of the independently funded studies showed harm from SSBs, while 93% of industry-funded studies showed no harm.

Coca-Cola is one of the world’s largest producers of SSBs, and the company spends a lot of money to make sure that “research” tells the story that Coke—and its billions of fans—want to hear.

Coca-Cola is one of the world’s largest producers of SSBs, and the company spends a lot of money to make sure that “research” tells the story that Coke—and its billions of fans—want to hear.

According to an article in the June 2018 issue of Public Health Nutrition, the Coca-Cola Company paid scientists more than $5 million for research that downplays the negative effects of SSBs. From 2008 to 2016, the soft drink giant funded 389 articles in 169 journals that support conclusions that physical activity is more important than diet as a risk factor for obesity, and that soft drinks and sugar are basically harmless.

The Oxford University researchers who analyzed Coke’s spending concluded: “Most of Coca-Cola’s research support is directed towards physical activity and disregards the role of diet in obesity.”

From 2010-2015 Coke funded almost $22 million on health-related research. During that period, the company put $98 million toward “community partnerships” promoting healthy physical activity, especially among young people.

The Coke-CDC Connection

Part of that money trail can be traced to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A July 2018 Forbes article showed that Coca-Cola gave $1 million to the CDC for exercise programs. Furthermore, emails between The Coca-Cola Company and CDC demonstrate the company’s efforts to influence the CDC for its own benefit, as noted in a January 2019 study published in The Milbank Quarterly.

Coke’s communications with the CDC, based on emails and documents obtained via the Freedom of Information Act, show the company’s interest in gaining access to the agency’s employees, influencing policymakers, and reframing the obesity debate by shifting attention and blame away from sugar-sweetened beverages and toward the problem of inactivity, according to a press release from the U.S Right to Know, a nonprofit consumer research group.

While lack of physical activity is, no doubt, a real public health problem, it is also a convenient dodge for a company wishing to avoid its share of responsibility in the obesity crisis.

The CDC has recently faced criticism for its links to other manufacturers of unhealthy products, including SSBs. The emails between CDC and Coca-Cola are especially egregious because they underscore the company’s efforts to “advance corporate objectives, rather than health, including to influence the World Health Organization,” the study says.

The paper concludes: “It is unacceptable for public health organizations to engage in partnerships with companies that have such a clear conflict of interest. The obvious parallel would be to consider the CDC working with cigarette companies and the dangers that such a partnership would pose.

“Our analysis has highlighted the need for organizations like the CDC to ensure that they refrain from engaging in partnerships with harmful product manufacturers lest they undermine the health of the public they serve.”

Up Front

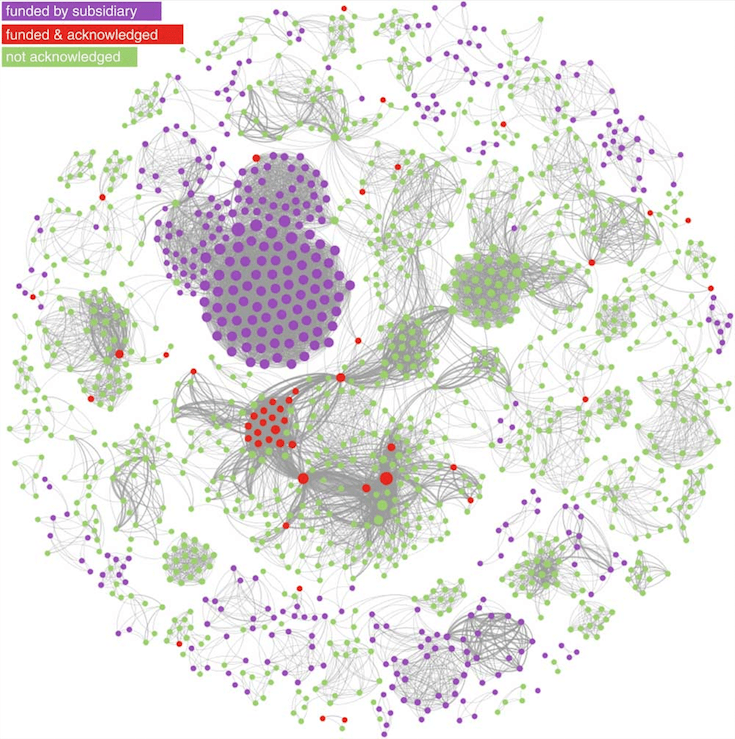

Another way Big Food has influenced science and policy is by creating or funding seemingly independent front groups to refute the negative studies on sugar, soda, and processed foods.

One such group is the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), which calls itself, “a pro-science consumer advocacy organization” committed to debunking “junk science,” combatting “scaremongering” and “chemophobia,” and supporting evidence-based science and medicine.

ACSH claims “a long and successful track record” in warning the public about the dangers of smoking, advocating for seat belt and bike helmet laws, and spearheading the effort to get Dr. Mehmet Oz dismissed from Columbia University’s faculty following his promotion of questionable “miracle” foods.

Dr. Hyman challenges ACSH’s “knight in shining armor” self-image.

He says this group is supported by the likes of Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Phillip Morris, Bayer and Monsanto—facts that were exposed several years ago by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), and again in 2013 by Mother Jones magazine, both of which published articles on the donors behind ACSH.

He says this group is supported by the likes of Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Phillip Morris, Bayer and Monsanto—facts that were exposed several years ago by the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), and again in 2013 by Mother Jones magazine, both of which published articles on the donors behind ACSH.

The organization says on its website that only 4% of its funding comes from donors. But according to the Mother Jones article corporate donors represent a much bigger chunk of ACSH’s treasury. “Internal financial documents provided to Mother Jones show that ACSH depends heavily on funding from corporations that have a financial stake in the scientific debates it aims to shape,” the article said.

Moreover, Dr. Gilbert Ross— the ACSH’s executive director for 18 years, and who served in that role at the time of the Mother Jones article—lost his license to practice medicine in New York State in 1995, after he was convicted in a scheme involving four sham clinics that defrauded Medicaid of roughly $8 million.

Another organization Dr. Hyman singled out is the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI). This is the group that funded a systematic review on sugar in the Annals of Internal Medicine concluding that current “guidelines on dietary sugar do not meet criteria for trustworthy recommendations and are based on low-quality evidence.”

In other words, “ILSI is saying the public shouldn’t pay attention to studies saying sugar is bad.”

‘Selfish Giving’

The “Sugar Wars” go back several decades, to the mid-1960s when Fred Stare, the person responsible for establishing the USDA’s Dietary Guidelines, wrote an article claiming that sugar was benign and that fat was the real enemy as far as nutrition and health were concerned.

This, says Hyman, is what ignited the obesity epidemic we are contending with today.

In terms of “selfish giving,” soda companies reign supreme. A 2013 report by CSPI, shows the soda industry’s targeted generosity  focused on civil rights or minority groups like the NAACP and the Hispanic Federation. But it certainly does not stop there. Over the years, Big Pop has given money to — and cultivated relationships with — groups representing doctors, dentists, dietitians, anti-hunger advocates, and others.

focused on civil rights or minority groups like the NAACP and the Hispanic Federation. But it certainly does not stop there. Over the years, Big Pop has given money to — and cultivated relationships with — groups representing doctors, dentists, dietitians, anti-hunger advocates, and others.

As the CSPI authors point out, corporate philanthropy is a great way for soda companies to buy friends, silence critics, and sweeten profits.

“Big Soda’s giving isn’t solely motivated by its love for the arts or its concern for minorities’ or anyone else’s health,” said CSPI executive director Michael F. Jacobson. “Makers of sugar drinks give to burnish their soiled reputations. They give so they can soften, or even silence, potential criticism. But mainly the industry gives so when provoked it can activate an instant Astroturf army to advance its extreme, anti-health agenda.”

The Cost of Bad Diets

According to Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, who wrote a May 2017 article on the JAMA Network, the health consequences of bad diets cost the US $1 trillion annually.

According to Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, who wrote a May 2017 article on the JAMA Network, the health consequences of bad diets cost the US $1 trillion annually.

“Across medical and scientific research, few areas are as relevant to health as food and nutrition. Suboptimal diet is associated with more deaths and disability worldwide than any other modifiable factor; in the United States alone, poor diet is linked to almost 1,000 cardiovascular and diabetes deaths per day,” said Dr. Mozaffarian, adding that “The challenges involving the role of the food industry in nutrition research are profound and not easily dismissed.”

On April 3rd, the Lancet released the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD 2017), with findings that echo Mozaffarian’s concerns. The GBD authors looked at dietary patterns and mortality rates in 195 countries, both rich and poor, and estimate that dietary risk factors such as high salt intake, low intake of whole grains, and low intake of fruits–kill roughly 11 million people a year worldwide.

It is the first time a major study has proposed that dietary factors have moved ahead of smoking and high blood pressure in terms of their death toll.

The GBD group—funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation—claims that more deaths in 2017 were caused by diets deficient in foods such as whole grains, fruits, nuts and seeds, than by diets filled with trans fats, sugary drinks, and high levels of red and processed meats.

That’s a surprising conclusion, and it would seem to exonerate soft drinks and processed foods. But it begins to make sense when one considers that in some countries covered by the study, there are no regulations for quantification and labeling of things like sugar, trans fats, and other harmful ingredients. In regions where labeling is required, regulations vary, making it difficult to quantify and assess the impact of these factors.

Further, the GBD group did not evaluate the impact of obesity as a form of malnutrition in its mortality calculations.

All that said, the GBD study is important in that it recognizes the profound impact of food on health and longevity. The authors stress an urgent need for coordinated global efforts to improve diet, through collaboration with various sections of the food system, and policies that drive balanced diets.

“This study affirms what many have thought for several years — that poor diet is responsible for more deaths than any other risk factor in the world,” says Dr. Christopher Murray, Director of the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, and one of the GBD authors.

“While sodium, sugar, and fat have been the focus of policy debates over the past two decades, our assessment suggests the leading dietary risk factors are high intake of sodium, or low intake of healthy foods, such as whole grains, fruit, nuts and seeds, and vegetables. The paper also highlights the need for comprehensive interventions to promote the production, distribution, and consumption of healthy foods across all nations.”

The Food Fix

What are the potential solutions to these global health problems? How can nutrition researchers and policymakers minimize the influence of Big Food companies that have clear profit motives and strong vested interests?

Despite his critical stance, Dr. Hyman stresses that, “The food industry is not monolithic. There are good and bad companies, as well as unintended consequences and deliberate actions.”

He called for a comprehensive reimagining of the entire food system, from regenerative agriculture, to growing more fruits and vegetables, to decreasing the use of pesticides, to overhauling biased government policy, to changing how we research nutrition. He believes medical practitioners have an important role to play in driving these changes.

According to a recent study published in PLoS Medicine, physicians’ prescriptions for healthy foods could help lower the risk of expensive chronic illnesses like cardiovascular disease and diabetes in Medicare and Medicaid patients. These programs together cover about a third of all US citizens.

Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a team led by Drs. Yujin Lee, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Renata Micha at Tufts University and Dr. Thomas A. Gaziano at Brigham and Women’s Hospital modeled the health and cost benefits of food prescriptions.

The researchers, supported in part by NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), simulated outcomes for two food incentives: a 30% subsidy for fruits and vegetables alone, and a 30% subsidy for a wider array of healthy foods including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, seeds, seafood, and plant oils.

If the fruit and vegetable-only incentive was carried out over a normal life span, the model estimated that the average consumption of fruits and vegetables would increase by about 0.4 servings per day, which would on a population basis prevent about 1.93 million cardiovascular events, and save almost $40 billion in health care costs.

A more general healthy foods incentive carried out over a lifetime would increase fruit and vegetable intake by the same amount, but would also increase average whole grain consumption by 0.2 servings per day; intake of nuts and seeds by 0.1 servings; intake of seafood by 0.2 servings, and plant oils by 1.5 teaspoons. This would prevent about 3.28 million cardiovascular episodes and 120,000 cases of diabetes, and save Medicare and Medicaid more than $100 billion.

But computer-based simulations are one thing. Real world outcomes studies are another. Dr. Hyman sees a lack of well designed, independently-funded, long-term prospective studies in the nutrition field.

He called for more projects like the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), but with a nutrition focus. In its entirety, the WHI enrolled more than 160,000 postmenopausal women aged 50–79 years (at time of study enrollment) over 15 years, making it one of the largest US prevention studies of its kind, with a budget of $625 million.

A 2014 analysis of the estrogen-plus-progestin arm of WHI indicated a net return on investment of $37 billion, providing a strong case for this type of large, publicly funded population study.

Dr. Hyman closed his IHS talk by revealing the title and premise of his new book, Food Fix – How to Save Our Health, Our Economy, Our Environment and Our Communities.

“A big part of it is [about] reconnecting agriculture and health. Now we have an agricultural system that creates disease.” He hopes to be part of a movement to change that, and invited the functional and integrative medical communities to join him in that quest.

END