“It is easy to pull a trigger. And in these places there’s always someone willing to give you a gun,” says Dr. S. A. Decker Weiss, of what he’s observed in refugee camps throughout the Middle East.

“It is easy to pull a trigger. And in these places there’s always someone willing to give you a gun,” says Dr. S. A. Decker Weiss, of what he’s observed in refugee camps throughout the Middle East.

“There are more weapons in places like Syria and Iraq than books. And it’s hard to learn to read, when you’re not able to sleep through the night.”

That’s the reality for hundreds of thousands of children living in refugee camps throughout the Middle East and other strife-torn regions. They live amid trash and vermin. All day, they breathe diesel fumes and burning tire smoke. The food is dismal, and the sanitation makeshift. In many places, they have only the barest protection from the elements, or from people who would harm them.

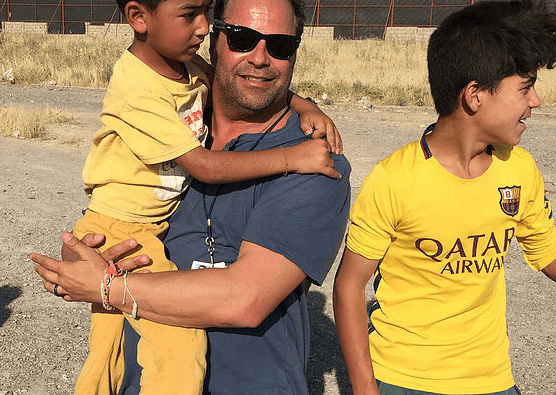

Over the last 4 years, Weiss has made multiple medical visits to refugee camps in Iraq, Jordan, Gaza, Israel and Lebanon, as well as in more stable but still difficult places like Rwanda, Senegal, and Haiti/Dominican Republic.

What he’s witnessed has reframed much of what he thought he new about medicine, sociology, and politics.

He’s seen first hand how extreme conditions provoke extreme biological responses that, in turn, translate into extreme behaviors. He’s witnessed how victims of violence so quickly become perpetrators of it. He’s been to places where abject poverty, poor nutrition, illness, lack of education, toxin exposure and the ever-present threat of violence keep people in states of hyper-reactivity or utter disconnection.

His experiences have led him to a profound conclusion: War is chronic inflammation writ large.

Intractable conflict is an autoimmune condition in the human social tissue. Like all autoimmune diseases, it emerges from self-defense mechanisms gone awry, and perpetuated by interlocking sets of feed-forward loops.

In short, Weiss—a naturopathic cardiologist based in Arizona–believes war is as much a medical issue as it is a political or economic one.

“Why aren’t physicians and medical people involved in peace talks? I now sit at these tables. I need to be there. More doctors need to be there,” Weiss told Holistic Primary Care.

There’s no doubt that ethnic/religious differences, economic disparities, and geopolitical gamesmanship play a role in war. But on the ground, in the lives of people who carry out–and suffer from–armed conflict, the principles of natural medicine have as much to offer as political “solutions.”

In an interview, Dr Weiss shared his “medical vision of peacemaking” centered on the notion that by quelling inflammation among individuals and removing—as much as possible—the environmental and social triggers, peace-making efforts can go much further than they’ve gotten with the usual political, economic, or religious agendas alone.

Peace Possible™, the non-profit organization Weiss founded earlier this year, provides medical services “for those who have nothing, or who have lost everything,” in some of the harshest places on the planet. But he and his team also study the antecedents of future conflict, the biological signals that drive people to violence.

A Dual Mission

A few years ago, Dr. Weiss was running a successful naturopathic practice in Scottsdale. As one of the nation’s few naturopathic cardiologists—an NMD with advanced training in cardiology—he was also in demand as a natural medicine consultant at conventional cardiovascular centers.

Without doubt, he was helping his patients. But after decades in the trenches of clinical practice, he felt a need to address health in the bigger picture. Like so many people drawn to medical careers, he wanted to heal the world.

This interest led him to Artis International, an interdisciplinary research group dedicated to improving the understanding of violence and conflict through field-based research, and to solving intractable conflict in areas perpetually at war.

Artis researchers, who’ve worked in 46 countries worldwide, bring the scientific method to the question of why people engage in politically motivated violence, especially when they have little personally to gain and so much to lose.

“One of the constant issues in these places is the radicalization of refugees,” says Weiss. “They (Artis) brought me in as a physician to start looking at why people in refugee camps are radicalizing.”

He says refugee camps are teeming with recruiters for various militias and sects that promise desperate young people a path –and a potentially glorious one–out of their current misery.

On an emotional level, it is not hard to understand how a young boy who witnessed his parents’ murder and his sister’s captivity, who has lived in limbo amid trash heaps and never learned to read or  write, who cannot envision a better life, could be lured by older and seemingly powerful men who promise decent food, a path out of squalor, and an opportunity for vengeance.

write, who cannot envision a better life, could be lured by older and seemingly powerful men who promise decent food, a path out of squalor, and an opportunity for vengeance.

Though many young refugees ultimately become new agents of violence, perpetrating on others the very trauma that destroyed their own families, many others do not. That’s the truly amazing thing.

Weiss is trying to understand in neurobiological terms what differentiates those who choose the way of violence from those who do not.

His initial work with Artis ignited in him a sense of passion and purpose. He sold his practice so he could devote himself full-time to what he views as a dual research and medical mission:

“I go in and try to see and treat as many people as I can. But I also get samples (blood and urine) so we can study biomarkers, to learn more about what’s happening physiologically to these people.”

Defining “Sacred Values”

Whether they are conscious of them or not, most people hold what Artis International co-founder, Scott Atran, calls “sacred values:” principles or people they will not abandon under any circumstance, and for which they are willing to die—or kill.

Atran, an anthropologist who is a leading foreign policy advisor on intractable conflict, says that to understand the perverse logic of war, one must understand the sacred values of its participants. These may be different for different people.

For some, sacred values center on a sense of “home”—however narrowly or broadly that is defined, or a sense of family honor. For others it is fidelity to a particular religious tradition or ethnic group. For still others it is a political or social ideal. These are the values that a person “refuses to sell.”

Activation of emotions around a person’s sacred values is mediated by two specific brain loci, and this is true regardless of what those values may be.

Using functional MRI, Atran and colleagues showed that brain activity around sacred values occurs primarily in the left temporoparietal junction and the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. They published their work in a provocative 2012 paper entitled, The Price of Your Soul: Neural Evidence for the Non-Utilitarian Representation of Sacred Values.

The left temporoparietal junction is heavily dopamine- and norepinephrine- mediated. The ventrolateral prefrontal cortex is also dopamine and norepinephrine-dependent, but it has a strong serotonin component as well.

Chronic inflammation, extreme stress, and poor nutritional status wreak havoc on all the neurotransmitter systems.

A Tale of Two Settlements

For the past few years, Weiss has been involved in a study comparing neurotransmitter and biomarker profiles of 50 young Syrian men relocated to a refugee community in Sweden with a similar cohort in the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan. Approximately 130,000 refugees live in Zaatari, located just over the Syrian border. It is now Jordan’s fourth largest “city”, and its most lawless.

The researchers are using urinary analysis to assess the three main neurotransmitters–serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine—and related metabolites. Urine-based methods are easy to use in the field, non-invasive, more stable than blood tests, and give valuable information about activity of the peripheral and enteric nervous systems.

The researchers are using urinary analysis to assess the three main neurotransmitters–serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine—and related metabolites. Urine-based methods are easy to use in the field, non-invasive, more stable than blood tests, and give valuable information about activity of the peripheral and enteric nervous systems.

Compared with the men resettled in Sweden, the Zaatari refugees show significant elevations in norepinephrine, and decreases in serotonin. They also show higher levels of 5-HIAA, a metabolite suggesting serotonin degradation.

Notably, there was no difference in average dopamine levels between the two cohorts, though the Zaatari group showed slightly higher levels of DOPAC, a product of dopamine degradation that is also a biomarker of oxidative stress.

In general, the neurotransmitter profiles of the Zaatari group showed a predisposition toward excitatory states, though there was considerable individual variation in both populations.

The researchers also collected data on subjective moods and tendencies toward action, based on participants’ self-assessments. This yielded interesting findings.

Roughly 60% of the men in the Jordanian camp indicated an inclination toward violence as a way of bettering their lives. In Sweden, that figure was 20%. The Zaatari cohort was also somewhat more inclined to see joining a military group as a path forward (20% vs 15%).

But what was really surprising was the fact that the sense of hopelessness was much higher in the Swedish cohort (84% vs 50%). In the Zaatari camp, hope is a 50/50 prospect, Weiss says. But the scary thing is that the sense of hope in Zaatari is strongest among the men with the strongest inclination to violence.

In both locations, the guys with the strongest tendencies toward violence showed the highest levels of excitatory and inflammatory neurotransmitters, with concurrent lower levels of calming and mood regulating biomarkers.

Refugees in Sweden who experience hopelessness or a sense of “giving up” also showed deficits in serotonin and other mood regulatory biomarkers, as well as low dopamine levels.

Neutralizing “Free Radicals”

Though these findings are preliminary, and it is impossible to reduce the complex reality of a refugee’s experience down to a handful of neurotransmitter changes, this line of work does open up a new way to think about war and those affected by it.

People may debate about the political, economic, or ethnic antecedents of armed conflict, but from a neurological perspective those don’t matter much. The physiological changes are similar regardless of the stated reasons for the fight.

Weiss explained that exposure to violence activates the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the immune system as an inflammatory response, which generates free radicals—an interesting term that’s equally applicable at the biochemical and sociopolitical levels.

He, and others involved in this emerging field of study, believe that the sequelae of war and violence are “treatable.” On the ground, he’s seen first hand what good nutrition, plenty of antioxidants, electrolytes, probiotics, and reduction o f toxin loads can do.

f toxin loads can do.

His vision for Peace Possible (P2) is to create, “a natural medicine-based medical NGO (non-governmental organization), one that fills the gaps left by other medical organizations rooted in conventional allopathic thinking.

“It can’t be just, “Go in, treat, and leave.” The thing is to get those populations self-sufficient, as much as possible,” says Weiss, acknowledging that this is a daunting task, given the magnitude of the refugee crisis.

“When I go into a community with a medical team, I first try to find out what they’re already good at, what they are doing well. And I don’t mess with that. We let them do what they do well. Then we assess what we can add that will benefit them, and be sustainable.”

He tries hard to hold to the fundamental principle of naturopathy: “First, do no harm.”

“You can’t go in and make the population worse. If you go in there and do nothing but pharma, and give them nothing but Cipro for every infection, then their gut microbiomes are disrupted, their serotonin levels drop, and you’re just adding to the problems.”

The Strongest Thing in the World

Peace Possible collaborates with other grassroots NGOs all over the world. Most recently, Weiss teamed up with The Great Need, a Christian organization founded by Tom Shiflet to provide aid to orphans and refugee children.

Guided by the Biblical verse, “Speak up for those who have no voice; come to the defense of those who are being crushed.” (Prov. 31:8), The Great Need delivers food, fresh water, clothing, medical supplies, toys, and love to young refugees in Iraq and most recently in the Dominican Republic. Weiss has served as a physician in both regions.

The work is extremely demanding. In an interview with Jigsaw Health, an Arizona nutraceutical company that is among Peace Possible’s key supporters, Weiss recalled his experiences in Iraq.

“They are long days and you’re really hot and you’re carrying equipment. Then you’re behind a table. They say there’s air conditioning, and it drops it from about 100 to about 95.”

The medical demand is overwhelming, the support is minimal, and the stories are heartbreaking. There’s little rest, and the sounds of war echo in the distance. But Weiss says the resilience of the people—especially the kids—is deeply inspiring.

“There’s one girl that really stands out. She was about 12 years old. She was kidnapped by ISIS. She was a slave, which involved everything from living on the floor in garbage to being repeatedly raped. She had some medical conditions and I worked with her. But she was saying all these English words to me.

“I was like, “Where’d you learn English?” She said, through a translator, that they had American magazines, and she was trying to learn English. She’s like, “I will not let these people ruin my life. There are good people in the world. There are people who care. I’m not going let two years of my life ruin the rest of it. I’m going to learn English, I’m going to go to America, I’m going to go to university and I’m going to come back here and I’m going to fix it. And I thought working my way through med school was tough!”

Though life in a refugee camp—even for just 3 weeks—gives plenty of reason for despair, Weiss says he returns humbled by the strength of his young patients.

“The human spirit–and the spirit of the young women especially– is the strongest thing in the world. I don’t think there’s anything more powerful. You get some of these young women that have gone through terrible things, and there is no stopping them. They not only hold onto hope, they want to fix the world and give hope back.”

At the same time, he worries about the fate of so many young refugees trapped indefinitely in highly toxic, violent, dead-end situations. The longer an individual stays in a refugee camp, the greater the risk that he or she will be susceptible to radicalization and recruitment.

He’s particularly concerned about the Rohingya, a Muslim-majority ethnic group that has lived for thousands of years in Myanmar (Burma). Over the last 3 years, brutal persecution perpetrated by the Myanmar government and its Buddhist majority has driven well over 600,000 Rohingya over the border into Bangladesh, where they live in extremely squalid makeshift camps.

“Al Qaeda is recruiting heavily there,” says Weiss. “We need to understand that.”

He hopes that by bringing the principles of holistic and naturopathic medicine into the equation he can help—at least in some small way–to break the physiological and psychosocial inflammation cascades that perpetuate that most vexing of human diseases: intractable war.

END